- works

- installations

- texts

- books

- videos

- publications

- events

- bio

- contacts

|

NORD a été réalisé grâce aux soutiens du Crédit du Nord, du CRT Nord, de la Région Nord et de Vinci Parution : Avril 2016 Format : 25 x 30 cm Français / Anglais Relié couverture cartonnée et en relief 38 photos 80 pages ISBN 979-10-95118-01-5 Rupture de stock Sold out |

|---|

Texte de Bruce Bégout

ENTRE ABSTRACTION ET EMPATHIE - Bref essai sur le paysage-ambiance

BETWEEN ABSTRACTION AND EMPATHY - A Brief Essay on Landscape as Ambiance

1. Devant/dedans

1. In Front/Inside

La pensée du paysage rayonne depuis quelque temps dans l’esthétique et la géographie, l’urbanisme et l’écologie. En un sens, elle a repris le flambeau d’une compréhension ambiancielle de l’environnement. L’idée d’une présence expressive de l’entourage se perpétue en effet dans les conceptions contemporaines du paysage. Les hommes sont des êtres qui, avant de tirer des flèches théoriques et de lancer des javelots pratiques, hument l’air. Chez eux, la compréhension tonale flaire le monde avant de le contempler ou de le transformer. L’affect précède toujours l’idée et le projet. C’est à partir de sa tonalité primordiale que s’élaborent les représentations, que se fomentent les entreprises. L’attrait moderne pour le paysage confirme ainsi la culture ambiancielle du thymique. Notre sensibilisation à ce qui nous environne et que, bien souvent, nous ne remarquons pas, hypnotisés que nous sommes par les intérêts pratiques, éclaterait dans notre capacité de nous ouvrir à l’Englobant, de le rassembler sous une vue agréable et émouvante : le paysage. Ce dernier n’est-il pas l’exemple même d’une situation affective, de l’effet sentimental de l’entourage sur les sujets ?

A great deal of thought about the landscape has been going on of late in fields such as aesthetics, geography, urbanism and ecology. In a sense, this work represents a continuation of the view that the environment can be understood in terms of ambiance. The idea that one’s surroundings are an expressive presence is perpetuated in contemporary conceptualizations of the landscape. Before the arrows of theory begin to be shot and the javelins of practicality thrown, humans are beings who breathe: beings for whom tonal understanding gets the scent of the world before the latter is contemplated or transformed. There is always affect before there is an idea or a project. Representations are elaborated and undertakings are devised by means of such primal tonality. The modern attachment to the landscape simply confirms the cultural embrace of ambiance as mood and humor. Our sensitivity to our surroundings - which we nevertheless so often do not notice, mesmerized as we are by practical interests - erupts in our ability to open ourselves up to the All-Encompassing, and then to gather it together in a pleasant and moving tableau: the landscape. For is the landscape not the very example of an affective situation, of the emotional effect that the surroundings have on subjects?

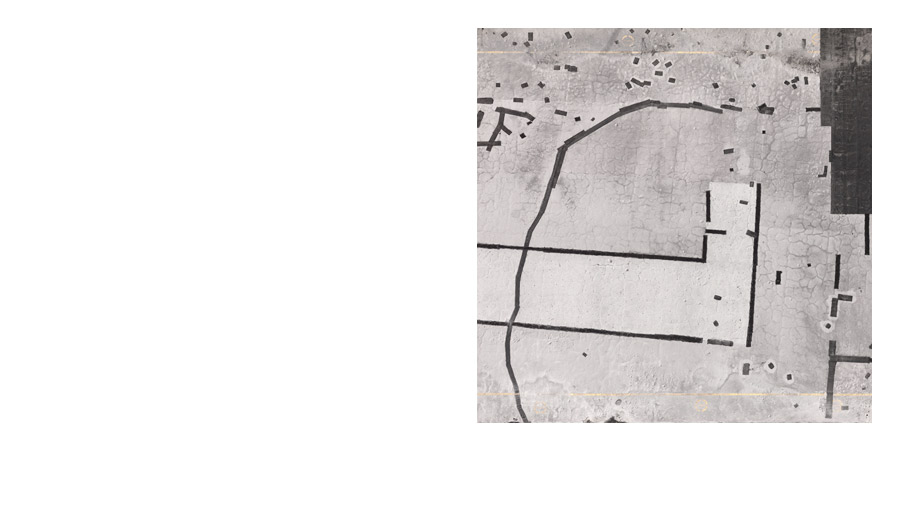

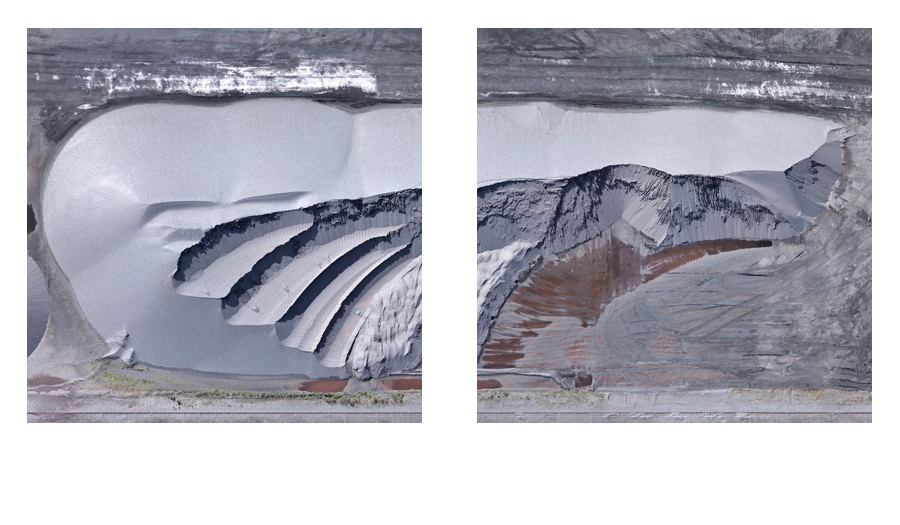

Pourtant l’ambiance ne paraît pas converger entièrement avec le paysage. Phénoménologiquement parlant, elle ne se manifeste pas tout à fait de la même manière. En effet, elle n’implique pas la même attitude chez le sujet qui la ressent. L’homme pris dans l’ambiance ne l’objective pas comme un simple paysage qu’il contemple et goûte. Il est plutôt absorbé en elle, et subit ses modulations affectives. Lorsque je vis l’atmosphère joyeuse d’une fête, je ne perçois pas le lieu, les convives, les éclats de rires et les danses comme formant un paysage, si touchant soit-il. Si tel était le cas, cela signifierait que je ne participe plus vraiment à cette ambiance mais que je m’en fais simplement une représentation neutre et distante. Je deviendrais alors spectateur d’une atmosphère, et non son agent direct. L’immanence absolue qu’implique l’ambiance, et qui la rend si proche et si intime, est précisément ce qui est rompu lorsque le paysage apparaît. L’attitude, esthétique ou écologique, qui se rapporte au paysage nécessite par conséquent la suspension de toute immersion ambiancielle. C’est en neutralisant la tonalité fondamentale de la situation, en s’extrayant de sa pression, qu’elle peut amener à la vue quelque chose comme un paysage. C’est par ce pas de côté que ce dernier se constitue. Tout paysage est une ascèse, un arrêt de l’immersion vitale et pratique. L’homme peut suspendre son implication dans la vie et s’ouvrir à la contemplation de ce qui l’entoure. En refoulant ses pulsions et ses besoins, en refusant de laisser libre cours à ses intérêts, il accède à la theoria, au spectacle de l’être. Il déréalise d’une certaine manière sa propre situation pour la voir comme telle. Ce que toute contemplation véritable délivre, c’est justement ce comme tel, ce qui est donné comme il est donné. C’est la raison pour laquelle le paysage est proche de la vision théorique1. Devant le paysage, je perçois ainsi une vie à laquelle je ne participe plus directement, que je ne partage pas affectivement et de manière pragmatique, mais dont j’apprécie la vue. Les photographies de Jérémie Lenoir accentuent cette impression spectaculaire d’un monde sous cloche, sans profondeur ni échappée, d’une planéité totale qui déréalise l’enregistrement mécanique des vues aériennes. Les sites vernaculaires, saisis à 1500 pieds de hauteur, révèlent leur aspect théorique, cette fête du regard sans concept ni utilité. Bassin, Auby, 2015 exhibe les aplats de couleur d’une sorte de Motherwell géologique. Stockage, Villeneuve d’Asq, 2015 lorgne vers l’expressionnisme abstrait. Le paysage se dégage du pittoresque pour se livrer au pictural pur.

However, the notion of ambiance seems not to converge completely with the landscape. In phenomenological terms, ambiance does not manifest itself in exactly the same way and does not imply the same attitude in the subject who experiences it. A person caught up in the ambient surroundings does not objectify them as a simple landscape to reflect upon and appreciate. Instead, s/he is absorbed into the ambiance and undergoes its affective modulations. When I experience the happy mood of a party, I am not aware of how the setting, the other guests, the laughter and the dancing come together to form a landscape, however moving it may be. If I become aware, it would mean that I was no longer really participating in the ambiance; I would merely be making a neutral and distant representation of a scene. I would thus become the spectator of an atmosphere rather than its direct agent. The absolute immanence implied by ambiance, which makes it so proximal and intimate, is precisely what is broken when the landscape appears. The aesthetic or ecological attitude inherent in the landscape therefore requires a suspension of all immersion in the ambient. Something like the landscape comes in the neutralizing of the fundamental tonality of a situation and removing oneself from its pressure. Such stepping to the side is what allows a landscape to be constituted. Every landscape is an ascesis, a breaking with an immersion in the vital and the practical. A person can suspend his or her involvement with everyday life and open up to contemplating his or her surroundings. By repressing drives and needs, by refusing to give free rein to interests, one accedes to theoria, to the spectacle of being. One’s own situation must by undone, in a sort of derealization so that it can be seen as such. This is what every true form of contemplation provides: exactly this as such that which is what it is. This is why the landscape has such an affinity with the theoretical1. When I stand before a landscape, I see a life in which I am no longer actively participating, one whose affective experiences and pragmatic concerns I no longer share, but which I find pleasant to regard. Jérémie Lenoir’s photography accentuates this spectacular impression of a world under glass, one lacking depth and vistas, a planar flatland in which the mechanical recording of aerial views is derealized. Indigenous sites, captured from a height of 1500 feet, reveal their theoretical facets in a nonconceptual and purposeless feast for the eye. Friche, Tournai, 2015 presents planes of colors in the style of a geological Motherwell. Stockage, Villeneuve d’Ascq, 2015 sets its sights on abstract expressionism. The landscape is disengaged from the picturesque, which gives way to the purely pictorial.

Sans vouloir ajouter ici une nouvelle contribution à la théorie du paysage, nous souhaiterions toutefois mettre en exergue ce qui nous apparaît comme étant deux de ses aspects les plus fondamentaux : a) le paysage implique tout d’abord un détachement d’une totalité plus grande, pays ou monde, dont il se distingue. Tout paysage surgit comme une section du cosmos donnée à voir. Il découpe le pays en tranches qu’il offre à la vue. Le cadre, ou la fenêtre, comme on l’a souvent noté, aide à ce détachement latéral en facilitant la constitution indépendante de cette portion visible. En effet il circonscrit le champ du paysage, lui donne un horizon qui peut certes s’ouvrir sur l’infini, mais toujours avec les moyens du fini. Sans cette «délimitation»2, il n’y aurait pas de paysage du tout. Ce dernier réclame donc cette unification/totalisation qui fait de la partie un tout. Mais ce travail, réel ou figuré, de sectionnement ne suffit pas. Un paysage ne se réduit pas à une contrée, à un morceau de pays identifiable. Il lui faut pour être paysage quelque chose de plus ; b) le paysage ne se détache pas seulement de ce qui l’entoure, mais aussi et avant tout de celui qui le contemple. La seconde opération constitutive du paysage ne consiste pas à le dégager de l’environnement familier, mais à le mettre à distance de celui pour lequel il peut y avoir paysage. Par là-même la partie dégagée devient visible comme telle, s’institue en spectacle. La distanciation crée l’espace nécessaire à la vision paysagère. Si le détachement latéral sépare le paysage de ce qui est voisin, le détachement profond le soustrait à ce qui est proche. C’est grâce à cet éloignement que le paysage naît sous les yeux. C'est seulement quand le sujet s’extrait de l’ici et maintenant qu’il peut se le figurer de novo sous la forme d’un spectacle3. Lorsque l’utilité domine et impose ses vues, lorsque les ambiances fortes absorbent les individus, le paysage ne peut encore apparaître. Penser l’émergence du paysage, c’est dès lors prendre en considération ce mouvement du spectateur qui, reculant d’un pas, voit apparaître devant lui quelque chose de nouveau dont il n’avait pas préalablement conscience. Le spectateur doit sortir du pays pour le voir comme paysage (cette sortie pouvant être purement visuelle, relever d’un simple changement d’attitude). Cette seconde opération de recul est fondamentale. Elle manifeste la résistance libératrice à l’absorption affectivo-pratique et ouvre l’espace possible de la représentation.

Without presuming to make a new contribution to the theory of the landscape here, I would nevertheless like to draw out what seems to me to be two of the most fundamental aspects of this theory: 1) first and foremost, the landscape implies a detachment from a larger totality of world or land, from which it is differentiated. Every landscape emerges as a section of the cosmos that is shown. It cuts the land into slices that are laid out for viewing. The frame, or the window, as has frequently been noted, facilitates such lateral detachment by allowing a portion of the visual field to be constituted as independent. It serves to circumscribe the field of the landscape, thereby providing a horizon that can certainly open out onto the infinite, but which always does so by using finite means. Without this “delimitation”2 there would be no landscape whatsoever. The landscape demands the unification and totalizing that transform the part into a whole. Yet this real or figurative work of selection is not itself sufficient. A landscape cannot be reduced to an area or region, to a bit of identifiable countryside. To be a landscape, something more is required, which brings us to the second point: 2) a landscape is separate not only from that which surrounds it but, above all, from the person who beholds it. The second constitutive operation involved in the creation of a landscape does not consist in disengaging it from a familiar environment, but instead in setting it at a distance from the person for whom it can become a landscape. In the same gesture, the part that is disengaged becomes visible as such. It is established as spectacle. This distanciation creates the space required by the vision that sees landscape. If lateral detachment involves separating the landscape from its neighboring environs, depth detachment involves subtracting it from that to which it is close. This distanciation is what allows a landscape to come into being before our eyes. It is only when the subject extracts itself from the here-and-now that the latter can be represented anew, in the form of a spectacle3. When utility has the upper hand and imposes its views, when individuals are absorbed into intense ambiances, landscapes cannot yet appear. To think about how landscapes emerge is to consider the movement of the spectator: the spectator, in stepping back, sees something new appear, something of which s/he was previously unaware. The spectator needs to take leave of the land in order to see it as a landscape (leaving can be purely visual, can be a simple change in attitude). The second movement backwards is fundamental. It is an expression of the liberation that comes from the resistance to being absorbed in emotional and practical concerns, a resistance that opens up a space for representational possibility.

Tout paysage, même vernaculaire, est un dépaysement. Il présuppose un effort de retrait, de déracinement voulu par rapport à son milieu natal, presque une errance du regard. C’est la séparation qui, l’éloignant du proche et du voisin, le crée dans sa forme propre. Le cadre ne suffit pas ici, il faut que la personne se replie légèrement de sa position antérieure, ne serait-ce que pour le voir comme cadre et contempler ce qu’il encadre. De nombreux commentateurs ont signalé dès le XVIIIème siècle qu’il n’y a de paysage que pour l’étranger, celui qui, n’appartenant pas à la région, la perçoit alors comme un objet original de plaisir ou de déplaisir esthétiques. Le paysage naît ainsi de la mobilité ; il est la vision de ceux qui migrent. L’autochtone, courbé depuis toujours sur ses soucis, ne discerne pas autour de lui des paysages. Il est accaparé par les travaux et les jours, submergé par les atmosphères locales qui le portent. A aucun moment, il ne regarde ce qui l’entoure comme un paysage. Il le ressent, le maudit, l’exploite, y projette ses attentes et ses tracas, mais ne le contemple pas. Il ne lui viendrait jamais à l’idée que le terrain qu’il arpente tous les jours soit un paysage. Pour les autres, peut-être, mais certainement pas pour lui qui vit, agit et souffre ici. Aussi tout paysage, dès qu’il apparaît, s’apparente-t-il à un voyage, à une certaine façon de quitter le pays, de prendre ses distances, parfois en restant sur place. Il suffit que le regard change, que le recul de la contemplation s’opère. C’est un arrachement qui contredit l’attachement viscéral au lieu et permet l’apparition du monde.

Every landscape, even those depicting the one’s own neighborhood, provides a change of scenery. Each presupposes an effort to withdraw, a wish to uproot oneself from one’s native milieu, and something akin to a wandering gaze. Separation, in which there is a pulling away from neighbors and those to whom we are close, brings this about in its rightful form. The presence of the frame does not suffice here. Instead, one must, to some extent, back away from one’s prior position, if only for the sake of seeing how it functions as a frame and thinking through what is in the frame. Since the eighteenth century, many writers have noticed how the landscape only exists for the foreigner, the person who does not belong to the area and therefore perceives it as an original object of aesthetic pleasure or displeasure. The landscape has its source in mobility; it is what migrants see. The home-grown native, who has always been shaped by personal problems and worries, simply does not see that there are landscapes all around him. Locked into works and days, submerged by the parochial atmosphere that bears him, he does not, at any point, view his surroundings as a landscape. He may feel them, curse them, cultivate them, and project his hopes and fears onto them, but he cannot see and contemplate them. He never forms the idea that the ground over which he strides each day is a landscape. Perhaps others can have such thoughts, but he, the one who lives, acts and suffers here, certainly cannot. Further, each landscape, as soon as it appears, becomes a voyage, a way of leaving home, getting distance, sometimes while remaining in the same place. All that is necessary for contemplation, as a movement backwards, to come into play is for the way of seeing to change. It is enough for the way of seeing to change for the retreat that is contemplation to come into play. This is a kind of rending, which contradicts the visceral attachment to place and enables the world to appear.

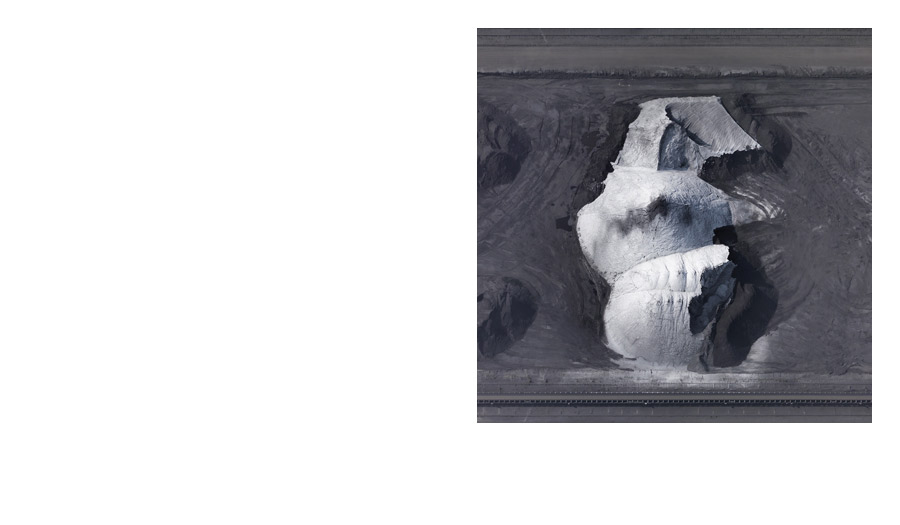

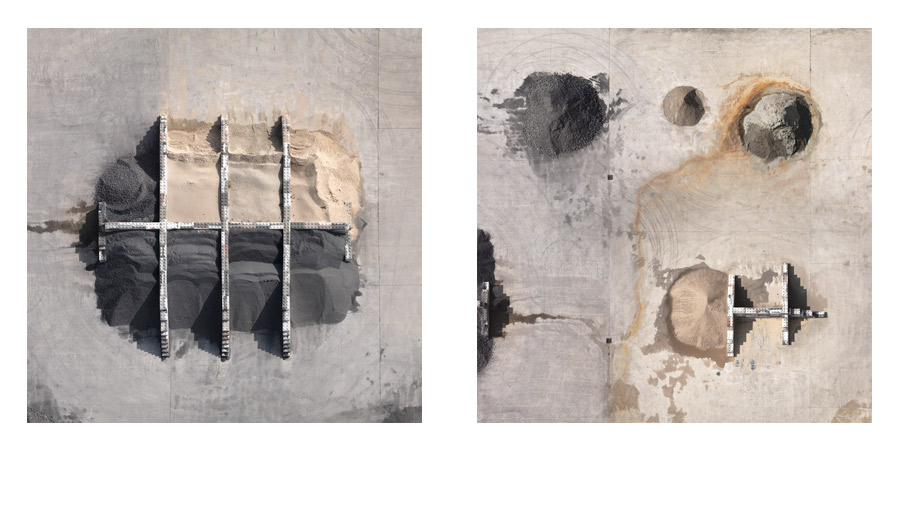

L’attitude esthétique qui donne naissance au paysage suspend l’attitude ambiancielle qui s’épanouit dans le contact fusionnel. C’est le refoulement de cette immersion tonale qui aboutit à la constitution du paysage. Sur le deuil de l’enveloppement, émerge la distance perceptive fondatrice de la délectation esthétique. L’ambiance ne délimite jamais, elle se donne constamment dans une diffusion sans bornes qui amalgame le monde et le sujet. Elle ne supporte pas la séparation et le retrait. Elle n’attire pas, elle emballe, cajole ou caresse. Or le paysage commence là où l’Enveloppe se déchire. Il est le fils de la scission. Le simple fait de tracer un sillon dans le sol le rend déjà possible. Car il est toujours le résultat d’un prélèvement géographique, d’une délimitation du milieu. Le paysage, précisément parce qu’il repose d’abord sur la distance entre le spectacle et le spectateur, empêche leur coïncidence. La fusion ambiancielle supprimerait sa condition première et fondamentale. Et c’est pourquoi le paysage comme tel inhibe toute absorption. A cet égard les sens de la proximité (goût, odorat, toucher) ne peuvent donner lieu à des paysages. Rien de ce genre ne leur correspond. Ils sont incapables de fournir des paysages gustatifs ou tactiles. Inversement l’interdit du contact est la condition sine qua non du paysage. Ce n’est pas seulement devant un paysage-tableau qu’il est écrit «ne pas toucher», mais devant tout paysage, artistique ou naturel. Or ce n’est pas tant le paysage qui clame noli me tangere que le spectateur qui, retirant sa main, modifie sa vue dans ce retrait. De même que le paysage ne touche plus le pays dont il s’est détaché réellement ou visuellement, il ne touche plus vraiment les hommes qui le vivent. Tout contact direct avec lui est impossible, et c’est dans l’intervalle creusé par cet écart que naît l’approche spécifique qui institue un bout de terre, si grand soit-il, en paysage. Ce n’est pas uniquement au fond du tableau que se situe le point de fuite, mais aussi devant. Ce ne sont pas les choses qui nous fuient dans la perspective, mais nous qui nous éloignons d’elles pour les soumettre à une nouvelle objectivité. Si le regard peut ainsi se perdre dans les horizons infinis du paysage, c’est qu’il s’est déjà lui-même extirpé de son milieu habituel où alors, lié à la main, dans une collaboration fonctionnelle, il circonscrivait le monde selon le découpage pratique de ses intérêts. Ainsi le paysage nécessite que l’homme se désolidarise du monde ambiant de l’ustensilité, pour, dans cette suspension, contempler ce qui n’est plus vraiment son environnement quotidien. Ce retrait sera complet, par exemple dans certaines gravures et aquarelles du jeune Dürer, lorsque le paysage lui-même deviendra un désert total et ne présentera plus les scènes minuscules du commerce humain, mais exhibera l’espace vierge et froid. C’est parce qu’il prend du recul sur son immersion affectivo-pratique dans la situation, jusqu’à s’éloigner parfois très haut dans le ciel, que se dévoile à lui, dans une vue plongeante d’oiseau, le paysage dans toute son ampleur. Autrement dit, le paysage à ses origines exprime le divorce de la terre et des résidents, et ce afin de révéler le monde. Sa vérité réside dans cette fracture du spectateur et de la nature environnante4. C’est par le déplacement, latéral et profond, bref par la découpe et le retrait, que naît ce regard singulier en Occident5. Les photographies de Jérémie Lenoir corroborent cette tendance au détachement du regard en réduisant le paysage à un graphisme abstrait qui lorgne du côté de la peinture non figurative. La sensation paradoxale qui émane d’Extraction, Gand, 2015, ou de Carrière, Flines-Lez-Râches, 2015, est celle de la fascination pour la visibilité pure. Même le détail insignifiant d’un camion, Stade, Lens, 2015, rappel subtil de la miniaturisation des éléments humains dans les premiers paysages flamands, n’estompe pas l’impression d’un flottement vague et sans motif, d’une dilution de l’objectivité dans la planéité.

The aesthetic attitude that gives rise to the landscapes involves a suspension of the ambient attitude that thrives in fusional contact. Repressing such tonal immersion is what leads to the constitution of a landscape. The perceptual distance that founds aesthetic delight emerges on the basis of a mourning for the envelopment. The ambient is never delimited; it continually offers itself up to a boundless diffusion where subject and world are confounded. It cannot stand separation and withdrawal. It does not attract; it encloses, clings and caresses. Now, a landscape begins at the place where there is a tear in the Envelope. It is the offspring of splitting. The mere act of marking a line on the ground already renders it possible, for it is always the result of a geographical removal, of setting a limit on the milieu. The landscape prevents the spectator from coinciding with the spectacle, precisely because it is based first and foremost on the distance between them. The fusional character of the ambient cancels this primary and fundamental condition, and this is why landscapes as such inhibit any kind of absorption. In this respect, the senses that rely on proximity (taste, smell and touch) are not able to serve as the basis of landscapes. In the latter, nothing corresponds to these senses. They are unable to generate tactile or gustatory landscapes. The opposite holds true as well, for the prohibition of contact is the sine qua non of the landscape. The injunction “Do Not Touch” is not only placed beside paintings of landscapes; it can also be found alongside every landscape, whether artificial or natural. It is not so much that the landscape itself declares noli me tangere, but rather that the spectator modifies what she sees while she is pulling her hand back. Just as a landscape no longer touches the land from which it is really or visually detached, it also no longer truly touches anyone who experiences it. It is impossible to have any direct contact with a landscape, for it is in the space hollowed out by this gap that something comes to be: the specific approach that can turn a bit of dirt, whatever its size, into a landscape. The vanishing point is found not only in the background of the picture, but also in the foreground. In perspective, it is not things that flee from us, but rather we who move away from them, to submit them to a new objectivity. If the gaze can get lost in the infinite horizons of a landscape, it is only because it has already been uprooted from familiar surroundings, where, linked to the hand in a functional collaboration, it cut up and limited the world along the lines indicated by practical interests. The landscape requires us to dissociate ourselves from the ambient world of implements and implementation, and, while holding them in abeyance, contemplate something that is no longer truly the world of everyday experience. Such withdrawal reaches completion, for example in certain of Dürer’s early engravings and watercolors, where the landscape itself is transformed into nothing but a desert in which all the miniature scenes of human commerce have been replaced with blank, empty space. Because the artist takes a step back from being immersed in the practicalities and affects of life situations - sometimes to the point of ascending into the skies and adopting a bird’s eye view - the landscape can reveal its full scope. In other words, from its origins, the landscape has represented the divorce between the Earth from its inhabitants, and has done so in order to reveal the world. Its truth is located in the fracture between the spectator and his or her natural surroundings4. Through this lateral and depth-wise displacement - in short, by cutting up and stepping back - the singular point of view that typifies the West was born5. By reducing the landscape to an abstract graphic design that moves towards non-figurative painting, Jérémie Lenoir’s work confirms this trend towards the detachment of the gaze. A paradoxical sensation emanates from Extraction, Gand, 2015 and Carrière, Flines-lez-Râches, 2015, one that comes from the fascination with pure visibility. Even the seemingly insignificant detail of the truck in Stade, Lens, 2015, which subtly reminds us of the tiny representations of human elements in the first Flemish landscapes, does not lessen the impression that there is a vague, unthematic fluctuation, a dilution of objectivity, in flatness.

Là où l’ambiance plonge l’homme dedans, le paysage le dépose devant. L’attitude intentionnelle qui les caractérise se distingue clairement. Dans le premier cas, le sujet est entièrement immergé dans une situation affective qu’il ne perçoit jamais comme paysage, car, si c’était le cas, il modifierait aussitôt l’ambiance en spectacle, et ne la ressentirait plus comme telle. Dans le second cas, ce même sujet se détache de la situation vécue qui l’absorbe et commence à l’observer sous un autre aspect, celui d’un spectacle de l’objectivité dont il apprécie les qualités propres. Le passage de l’un à l’autre peut être facile et rapide ; il suffit de placer devant ses yeux une sorte de vitre transparente et de collaborer à ce que l’on perçoit sur le mode du spectaculum, tel Pétrarque au Mont Ventoux. Mais si la vitre tombe, l’immersion affective et pratique reprend aussitôt ses droits et entraîne de nouveau l’homme dans une participation proche, intime et englobante. Autrement dit, si le paysage devient trop sensoriel, si sa présence physique et émotionnelle est trop forte, il disparaît comme tel sous l’aspect d’une ambiance.

Where ambiance plunges us within, the landscape sets us down in front. There is a very different intentional attitude in the two. In the first case, the subject is completely submerged in an affective situation that will never be perceived as a landscape, for if it were, the ambiance would immediately be transformed into a spectacle, which would no longer be experienced as before. In the second case, the same subject breaks away from the lived situation in which s/he has been absorbed and begins to see it in a new way, one in which the spectacle of objectivity is appreciated on its own terms and for its own qualities. It is easy to pass from one of these cases to the other, and it can happen quite quickly. It is enough to place a sort of transparent window in front of one’s eyes and to collaborate with what is perceived in this mode of spectaculum, as Petrarch did on Mont Ventoux. Yet if the window falls down, immersion in the affective and the practical will once again have the upper hand and will again involve one in a close, intimate and encompassing form of engagement. If the landscape becomes too sensory, if its physical and emotional presence becomes too strong, it will disappear under the emergence of an ambiance.

2. Le caractère ambianciel du paysage

2. The Character of the Landscape as Ambiance

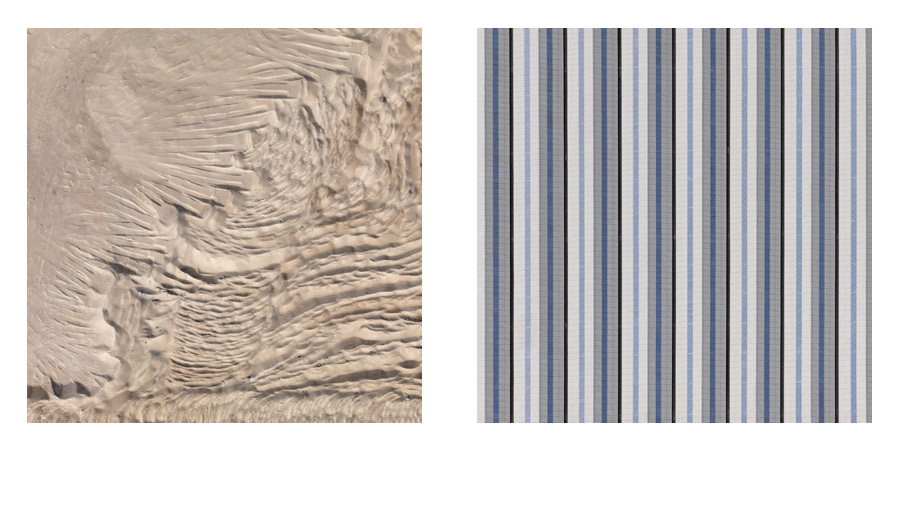

Mais le paysage n’est-il pas autre chose qu’une représentation ? L’émotion de saisir la totalité du monde, la passion de faire un avec ce qui se donne à voir, ne vibrent-elles pas toujours en lui ? Même les vues aériennes de Lenoir, qui pourraient être perçues comme un jeu graphique (Parking, Lesquin, 2014 ou Plate-forme, Valenciennes, 2014), irradient d’une chaleur attirante. Si le paysage naît à partir du recul, il ne demeure pas longtemps dans cette position. Il exprime aussi et principalement la projection du spectateur dans le spectacle, sa volonté de s’unir avec ce qui s’étale devant ses yeux. En un sens, le détachement rend possible l’élan fusionnel, mais il disparaît aussitôt en lui. L’amplitude des scènes de la nature et de la vie qui se dévoilent attire le regard ; elle l’absorbe. Il y a un effet d’entonnoir dans le paysage. Un vertige même de l’ampleur, de l’oubli du voyant dans le visible trop grand pour lui. Tout paysage envoie une invitation à se perdre. C’est une technique visuelle de désindividuation. L’émotion qui le caractérise n’excite pas le principe vital et égoïste de l’autoconservation ; elle titille plutôt l’affectivité tonale qui nous associe au monde. Il n’y a en lui ni pulsion ni sentiment, mais résonance diffuse. Aussi le spectateur ne reste-t-il jamais le sage théoricien qui observe l’être en tant qu’être, mais, dès que quelque chose se donne à voir à lui comme un paysage, il devient tout de suite un homme ému. S’il n’y avait pas ce plaisir immédiat de la vue dans son désir de saisie totalisatrice, il n’y aurait pas de paysage. Ce dernier est donc irréductible à la theoria qui neutralise les affections et les intérêts au profit de la recherche de la vérité.

It might be suggested that a landscape is nothing but a representation. The emotion of grasping the world in its entirety, the passion of becoming one with what one comes to see — are these not what always resonates through the landscape? Even Lenoir’s aerial shots such as Parking, Lesquin, 2014 and Plate-forme, Valenciennes, 2014, which can be read as a form of graphic play, give off a very appealing warmth. If the landscape has its origins in a stepping back, it seems not to remain in that position for very long. It also, and even principally, expresses how the spectator is projected into the spectacle, that is, the willingness to merge with what is unfolding before one’s eyes. In a sense, this impetus to merge is made possible by this very detachment, which immediately vanishes into the fusional. The amplitude of the scenes of nature and life that are revealed attracts and absorbs the gaze. The landscape has a funnel effect, a vertigo of scale, where the viewer is forgotten in the expanse of a visible that is too large for him/her. Every landscape is an invitation to lose oneself. It is a visual technique of deindividuation, characterized by an emotion that does not stimulate the vital and egoistic principle of self-preservation, but instead titillates the tonal affect that we associate with the world. It is neither a drive nor a feeling, but rather a diffuse resonance. The spectator never remains some sort of sensible theorist who observes being as such; from the moment that a landscape comes into view, this same spectator is moved by emotion. If there were no immediate pleasure of seeing in the desire to grasp everything as a totality, there would be no landscape. For this reason, landscapes cannot be reduced to the theoria that neutralizes affections and interests in the name of the search for truth.

Autrement dit, le paysage n’est pas une contemplation paisible et objective de la nature, mais une délectation de la vue à ce qui l’entoure. Le plaisir esthétique que procure le paysage dément le retrait et implique entièrement le spectateur dans ce qu’il voit. Cela n’est possible que parce que le paysage ne se présente jamais comme une unité fermée sur elle-même, mais, tout en valant et s’affirmant comme tel, il entretient une relation avec l’Un-Tout dont il s’est détaché. Croire que le détachement et l’unification suffisent à former un paysage est une erreur. Le paysage vibre comme paysage, en tant qu’il dialogue avec la totalité du monde dont il s’est coupé en prétendant valoir pour elle. Le paysage-mur des enluminures de la fin du Moyen Âge (les frères de Limbourg, miniatures des Heures de Turin-Milan, Les Très Belles Heures de Notre-Dame) s’ouvre sur le paysage-horizon de la peinture flamande (Patinir, Gérard David, Van Eyck). Il contient toujours une allusion à l’infini. La formation du paysage passe par la séparation de la partie puis par sa revendication comme totalité autonome, mais elle ne s’achève véritablement que lorsque le tout du paysage résonne avec l’Illimité. C’est grâce à cette relation entre la totalité formée et le tout primordial dont elle s’écarte, tout en voulant le représenter, que naît la respiration atmosphérique du paysage.

In other words, landscapes do not involve a peaceful and objective contemplation of nature, but instead a gaze that takes delight in what surrounds it. The aesthetic pleasure procured by landscapes belies the backwards movement, such that the spectator becomes implicated in what s/he sees. This is only possible because landscapes never present themselves as unified and closed in on themselves; while asserting that they are unified, landscapes nevertheless continue to have a relationship with the All-One [l’Un-Tout] from which they have been detached. It would be an error to think that detachment and unification are sufficient for forming a landscape. A landscape vibrates as landscape, insofar as it is in dialogue with the totality of the world from which it has been cut: it claims to have the same worth as and to stand for that world. Medieval illuminations of the wall-landscape (the Limbourg brothers, the miniatures of the Heures de Turin-Milan hours, the Très Belles Heures de Notre-Dame) open out onto the horizon-landscapes of Flemish painters (Patinir, Gerard David, Van Eyck). There is always an allusion to infinity. A landscape takes shape by being separated off as a part, which then claims to be an autonomous totality, but which only really attains this status when the landscape as a whole resonates with the Infinite. Through this relation between a formed totality and the primordial whole [tout] from which it is excluded even as it seeks to represent it, the atmospheric breath of a landscape is born.

On comprend dès lors que, du paysage, puisse émaner une atmosphère. Etant donné que le paysage attire le spectateur, il l’enveloppe pour ainsi dire dans son ampleur. Un paysage ne présente jamais une simple collection de choses. On ne s’attache que rarement aux détails qui le composent. Ce qui émeut tout d’abord en lui c’est la totalité donnée à voir. Or l’ambiance ellemême possède ce mode de manifestation holistique ; elle ne résulte pas de la somme de sentiments particuliers, mais elle imprègne la situation tout entière d’une tonalité affective particulière. La forme même du paysage comme totalité appelle donc l’ambiance. C’est parce qu’il est une totalité non agrégative que le paysage peut susciter immédiatement une atmosphère. Et cette totalité qui s’offre n’est pas un simple géorama, comme celui de Chardon6, mais une vue touchante qui parle d’abord aux sens avant d’instruire l’esprit. C’est dire que le paysage, né de la theoria, la dépasse et s’impose de manière indépendante de toute saisie cognitive. Rarement le spectateur d’un paysage naturel ou peint demeure dans un état d’observation sereine et distanciée. Il est plutôt captivé, séduit, troublé. Il abandonne la recherche de la vérité et de l’intérêt, et se laisse agréablement entraîner dans un flottement perceptif et affectif. Sans cette résonance thymique, le paysage en tant que tel ne se manifesterait pas. L’élément majeur du paysage réside donc, nous dit Simmel, dans «la Stimmung»7, dans l’émotion indéfinissable qui imprègne le spectacle et le rend si touchant. Cette Stimmung atmosphérique, brume sentimentale qui recouvre légèrement la vue et lui confère sa tonalité particulière, est le facteur unifiant du paysage ; c’est elle qui rassemble les détails et les fond dans l’impression d’ensemble. Elle colore toutes les parties d’un même sentiment.

We understand that, as of that point, an atmosphere can emanate from a landscape. It attracts the spectator, who is then enveloped, as it were, within its scale. A landscape never presents a simple collection of items. In fact, we rarely really notice the details that compose it. What moves us right away is the totality that it allows us to see. Now, ambiances as such also have a way of presenting themselves holistically. They are not the sum of the specific feelings that are their parts; instead, they completely permeate the whole of a situation with a particular affective tone. Even the form of the landscape as totality calls forth an ambiance. This is because the landscape’s non-aggregational totality is immediately evocative of mood and atmosphere. This totality is not a simple georama such as Chardon’s6, but rather a touching vision that speaks to the senses before educating the mind. The landscape surpasses the theoria from which it is born, imposing itself independently of all cognitive understanding. Viewing a natural or painted landscape rarely involves a placid and detached state of observation. Instead, the observer is captivated, seduced, even disturbed. The search for truth or for best interests is abandoned as one allows oneself the pleasure of being drawn into a zone where perception and feeling float freely. Without this attunement of mood, a landscape as such will not appear. The major feature of the landscape thus resides, as Georg Simmel says, in the “Stimmung”7: the indefinable emotion that permeates the scene and makes it so moving. This atmospheric Stimmung, the haze of feeling that tints vision with its own specific tones, is the unifying factor of a landscape, which brings the details and background together in a way that gives the impression that they constitute a whole. It imbues every part with the same feeling.

Comment comprendre cette dimension affective du paysage ? Où faut-il chercher le fondement de cette expérience à la fois esthétique et sentimentale ? Inspiré par les thèses des romantiques allemands, Simmel dévoile ce qui constitue à ses yeux le fondement de ce «curieux processus de caractère spirituel»8 qui aboutit à la naissance du paysage. Car tout repose en fin de compte sur un changement d’attitude, sur une conversion du regard. L’homme stimule sa sensibilité en lui donnant une vie extérieure. Le ressort caché de tout paysage consiste ainsi dans le retour de l’être aimé, à savoir soi-même. Il donne à voir la capacité totalisante d’un coeur qui embrasse le tout de la nature et en jouit comme d’une entité neuve et indépendante. Car, en se délectant à la vue de panoramas époustouflants, l’âme se donne une consistance objective, s’inscrit dans l’espace et se fait aussi grand que lui. Le philosophe de la Kulturkritik conçoit ainsi la Stimmung qui émane du paysage comme le résultat discret d’une projection subjective. A lire les analyses de sa Philosophie du paysage, on se rend compte en effet qu’est toujours à l’oeuvre ici, de manière subconsciente, un transfert de l’unité affective psychique vers le paysage lui-même. Dans son esprit, l’unité perceptive devient un paysage au moment où le sujet percevant la vit de manière affective. Même si, de fait, dans l’expérience esthétique du paysage, on ne peut distinguer d’un côté le sentiment subjectif et de l’autre les données objectives, tout cela étant mêlé dans l’expérience esthétique elle-même, on doit cependant continuellement présupposer une objectivation sous-jacente de la «force unifiante de l’âme»9. Il est certes mal à propos de poser la question de savoir «si notre vision unitaire de la chose est première ou seconde par rapport au sentiment concomitant»10, mais le paysage ne vit néanmoins que dans et que grâce à «notre activité créatrice». Il n’est en vérité que la production immédiate de cette Stimmung de l’âme qui s’exprime extérieurement dans le paysage. C’est le cas où l’unité affective du psychisme s’objective, comme par exemple dans un poème où, aussitôt vus, les mots reçoivent immédiatement, alors qu’ils ne sont que des signes sans vie, la chaleur du sens qui circule en eux. L’esprit possède ainsi cette capacité de produire en dehors de lui des réalités objectives avec lesquelles il s’amalgame totalement. C’est, comme pour toute formation culturelle, «l’acte psychique»11 qui crée le paysage, qui rassemble les données éparses, les unit et les plonge dans une tonalité affective propre.

How can we understand this affective dimension of landscapes? Where can the foundation of this experience, which is simultaneously aesthetic and emotional, be found? Georg Simmel, who was inspired by the German romantics, discloses what he finds to constitute the basis of the “curious process of a spiritual nature”8 that results in the emergence of the landscape. In the end, it all rests on a change of attitude or conversion of the gaze. Man stimulates his sensibilities by providing himself with an external life. The hidden motive in every landscape consists in the return of the loved one — that is, oneself. The heart can embrace the whole of nature and take pleasure in it as if it were a new and independent entity, and its capacity for totalizing is rendered visible. For as it delights in the view of breathtaking panoramas, the soul grants itself an objective consistency, expands, places itself within space and becomes as wide as it. This philosopher of Kulturkritik conceives of the Stimmung that flows out from a landscape as an understated effect of subjective projection. Reading the arguments of his text on the philosophy of the landscape makes one realize what is always at work here, subconsciously: the transferral of the affective unity of the psyche to the landscape itself. In his mind, perceptual unity becomes a landscape at the point where the perceiving subject experiences it affectively. Even if, in the aesthetic experience of the landscape, subjective feeling and objective data cannot, in fact, be distinguished, for they are blended together in the aesthetic experience itself, we should nevertheless continually presuppose that there is an underlying objectivization of the “unifying force of the soul”9. It would certainly be amiss to ask whether we can know “if our unitary vision of a thing is primary or secondary as regards its concomitant feeling”, but the landscape, nevertheless, has life only in and as a result of “our creative activity”10. In truth, that is nothing but the immediate production of Stimmung in the soul, which is expressed externally in the form of a landscape. This is what happens when the affective unity of the psyche is objectivized, as, for example in a poem where, as soon as they are seen, the words, which are, in fact, only lifeless signs, are bestowed with the glow of the meaning that circulates through them. The mind thus possesses a capacity to produce, outside itself, objective realities with which it coalesces completely. Just as with every cultural formation, the “psychical act”11 is what creates landscape by gathering scattered elements together, uniting them and immersing them within one’s own affective attunement.

Mais l’ambiance propre à un paysage, cette aura particulière qui le pénètre et nous enveloppe, est-elle réductible à une médiation psychique ? Il n’est pas facile de répondre à une telle question. Ce qui est sûr est que le détachement ne nuit pas à l’empathie ambiancielle. Tel est peut-être même l’enseignement profond des photographies de Jérémie Lenoir : l’extrême abstraction (de la hauteur, du refus de la figuration réaliste, de la picturalité pure) bascule dans l’attrait, dans la sensation d’enveloppement par le jeu des lignes et des couleurs. De l’extraction découle l’attraction. Le paysage suspend dans un premier temps les relations affectives et pratiques de l’individu au monde ordinaire pour l’élever ensuite à une forme supérieure de participation : l’union avec le cosmos. L’arrachement au pays (ici manifesté dans les photographies par la vue aérienne et le cadrage strict) n’est donc pas définitif, c’est une manière de se fondre dans la nature. Aussi le paysage réconcilie-t-il l’individu et le monde, met-il fin à leur scission théorico-pratique en les associant dans une unité supérieure. Seul ce retrait de la représentation rend possible la projection émotionnelle. Le spectateur recule pour mieux sauter. Il se désolidarise de l’ambiant pour s’abandonner à l’ambiance. Les historiens d’art le clament d’une manière unanime : l’aspiration visuelle que suscite le paysage, ce sentiment de bascule dans l’infini, provoque une extase du regard. Cézanne ne confesse pas autre chose à Joachim Gasquet. Faire taire les idées, réduire au silence les prénotions, et s’amalgamer pour durer, se fondre avec ce qui n’est pas soi. C’est par la sensation là encore que la représentation s’estompe et forme, dans cette disparition de la distance sereine, la plénitude du paysage. Ce que «j’essaie de vous traduire, dit Cézanne, est plus mystérieux, s’enchevêtre aux racines mêmes de l’être»12. C’est ce milieu prédualiste qu’il s’agit de restituer, de faire sentir. Non pas tant les formes et les forces que ce plan d’être et de vie au sein duquel elles naissent et se développent. Bien sûr revient parfois, en loucedé, la rengaine de la projection, des influences qui vont et viennent entre l’esprit et la nature13, mais tout cela s’efface rapidement derrière la présence vive de l’unité primordiale :

Yet can the specific ambiance of a landscape — the particular aura that permeates it and enfolds us — be reduced to a form of psychical mediation? This question does not have an easy answer. What is certain is that detachment does not harm the empathy of ambiance. This is perhaps the deepest lesson of Jérémie Lenoir’s photography: there is a shift in which extreme abstraction (of height, of the refusal of realistic figuration, of pure pictoriality) becomes appealing, in the sense of being enfolded within the play of line and color. From extraction there comes attraction. The landscape first suspends a person’s practical and affective relations with the everyday world, elevating it to a higher form of involvement: a union with the cosmos. The experience of being uprooted from the land — expressed here in the aerial image photographs and the strict framing — is not permanent; it is a way of melding with nature. The landscape also reconciles the person with the world, by putting an end to the splitting between theoretical and practical that divides them and bringing them together in a higher unity. Projection of emotion can only occur when there has been such a withdrawal through representation. The spectator steps back so that s/he can jump forward better. One dissociates oneself from the ambient in order to give oneself over to an ambiance. Art historians are unanimous on this: the way in which landscapes draw in the gaze and the feeling of falling into infinity elicits an ecstasy of vision. This is just what Cézanne described to Joachim Gasquet. Silencing one’s ideas and preconceptions, and blending oneself in order to abide with and melt into that which is other: it is once again through sensations that representations blur and take shape, in the vanishing of the placid distance that is the fullness of the landscape. As Cézanne said, “What I’m trying to explain is more mysterious. It’s tangled up in the very roots of existence [de l’être]”12. It is a matter of restoring the milieu that is prior to dualism, of making it tangible: not as forms and forces, but rather as the plane of being and life from which these are born and develop. Of course, the old clichés of projection — the influences that come and go between mind and nature13 — may creep back in, but all of that is quickly extinguished by the living presence of primal unity:

Pour bien peindre un paysage, je dois d’abord découvrir les assises géologiques. Songez que l’histoire du monde date du jour où deux atomes se sont rencontrés, où deux tourbillons, deux danses chimiques se sont combinées. Ces grands arcs-en-ciel, ces prismes cosmiques, cette aube de nous-mêmes au-dessus du néant, je les vois monter, je m’en sature en lisant Lucrèce. Sous cette fine pluie je respire la virginité du monde. Un sens aigu des nuances me travaille. Je me sens coloré par toutes les nuances de l’infini. A ce moment-là, je ne fais plus qu’un avec mon tableau. Nous sommes un chaos irisé. Je viens devant le motif, je m’y perds. Je songe, vague. Le soleil me pénètre sourdement, comme un ami lointain, qui réchauffe ma paresse, la féconde. Nous germinons.

In order to paint a landscape correctly, first I have to discover the geographic strata. Imagine that the history of the world dates from the day when two atoms met, when two whirlwinds, two chemicals joined together. I can see rising these rainbows, these cosmic prisms, this dawn of ourselves above nothingness. I immerse myself in them when I read Lucretius. I breathe the virginity of the world in this fine rain. A sharp sense of nuances works on me. I feel myself colored by all the nuances of infinity. At that moment, I am as one with my painting. We are an iridescent chaos. I come before my motif and I lose myself in it. I dream, I wander. Silently the sun penetrates my being, like a faraway friend. It warms my idleness, fertilizes it. We germinate.

A la fois naïf et rusé, Cézanne cherche à prendre à revers le cadre sémantique du sujet et de l’objet pour mettre au jour une «harmonie générale». Le thème de la «plaque sensible» et du peintre-récepteur ressortit à cette quête d’une fusion amicale, voire animale et végétale, avec toutes les choses. Contre la «rhétorique du paysage», Cézanne aspire à la disparition individuelle dans un «redevenir soleil», qui est aussi un redevenir-air, un redevenir-roche, un redevenir-lumière. Cette façon de laisser, dans les interstices du sol, scintiller le bleu du ciel confirme la volonté d’unifier le paysage par l’élément atmosphérique. Le peintre insiste à de nombreuses reprises sur cette dimension : rayonnement, respiration, souffle, flux. Une «logique aérienne»14 gouverne son art et sa vie. La relation même qu’il entretient avec le motif, notamment la Montagne Sainte-Victoire, relève entièrement de l’ambianciel, la «religion» du paysage, ce qui relie tout ce qui est dans une même émotion. C’est en effet un même mouvement sensible qui court à travers les choses et les individus :

Simultaneously naive and astute, Cézanne tries to get at the semantic frame of subject and object from behind, to bring a “general harmony” to the fore. The theme of the “photographic plate” and of the painter-receptor emerge from the search for an amicable [amicale] — or even animal [animale] and vegetal — coalescence with all the things that are. To the “rhetoric of landscape”, Cézanne opposes a yearning to disappear as an individual and to “become the sun again”, which is also a way of again becoming air, rock and light. This way of making the blue of the sky glimmer in the interstices of the ground confirms his determination to unify the landscape with the atmospheric element. He often accentuates this dimension of radiance, respiration, breath and flux. His art and his life were directed by an “airborne logic”14. His very relation with the motif, in particular that of the Montagne Sainte-Victoire, comes entirely from the ambiance, landscape’s “religion”, whereby all-that-is is conjoined in the same emotion. The same perceptible movement runs throughout people and things:

Quand la sensation est dans sa plénitude, elle s’harmonise avec tout l’être. Le tourbillonnement du monde, au fond d’un cerveau, se résout dans le même mouvement que perçoivent, chacun en leur lyrisme propre, les yeux, les oreilles, la bouche, le nez… Et l’art, je crois, nous met dans cet état de grâce où l’émotion universelle se traduit comme religieusement, mais très naturellement à nous.

When sensation is at its fullest, it is in harmony with all existence [tout l’être]. The world spinning in the back of the brain causes the same movement that is perceived by the eyes, ears, mouth and nose, each with its own poetry. And I believe that art puts us in that state of grace where universal emotion is expressed to us religiously somehow, but very naturally.

Se laisser entraîner par l’aura du lieu et du moment, se fondre dans l’émotion cosmique qui accouple les corps et les éléments naturels, faire vibrer la profondeur et s’inscrire en elle au point de disparaître, voilà le projet si mal nommé : «La nature parle à tous. Eh bien ! jamais on n’a peint le paysage. L’homme absent, mais tout entier dans le paysage».

Letting oneself get caught up in the aura of the moment and the place, dissolving into the cosmic emotion in which body and nature are coupled, making the depths vibrate and entering into them to the point where one disappears — this is the project that has been so badly named: “Nature speaks to everyone. Well, no one has ever painted the landscape, where man is absent, yet completely within the landscape”.

L’homme est aussi entièrement absent des photographies de Jérémie Lenoir, évaporé dans le dessin géométrique (Toiture, Aalbeke, 2014) et les aplats chauds de couleurs (Bassins, Béthune, 2014), dissous dans la forme pure et stricte qui défait l’opposition du réel et de l’irréel. Et pourtant cette absence est la condition même de l’immersion. On ne le voit nulle part, parce qu’il est présent partout, non dans le détail mais dans le tout, uni à lui, fondu en lui, et le spectateur lui-même n’occupe plus la position de surplomb de la vie aérienne, tranquille et sereine, il n’est plus dans sa pensée-belvédère à l’abri du contact, au contraire, il a chuté dans le visible, il s’est volatilisé dans l’atmosphère particulière de ces clichés si troublants qu’ils hésitent entre abstraction et empathie.

The human is also completely absent from Jérémie Lenoir’s photography; it has evaporated into the geometric design (Toiture, Aalbeke, 2014) and the warm planes of color (Bassins, Béthune, 2014), and has dissolved into the strict purity of form, where the opposition between real and unreal is undone. Yet this absence is also the very condition of being immersed. It cannot be seen anywhere because it is present everywhere, not in the detail but rather in the whole that is unified with it, merged into it. The spectator is displaced from the sky-high life, with its calm, serene position of aerial overview; emerging from that retreat, from the lonely belvedere of thought, s/he is plunged into the visible and vanishes into thin air, into the very particular atmosphere of these photographs, which are so disturbing in their vacillation from abstraction to empathy.

Bruce Bégout

1 - Sur ce point, nous renvoyons aux belles analyses de Joachim Ritter. Cf. Paysage. Fonction de l’esthétique dans la société moderne, collection "Jardins et paysages", Besançon, Editions de l’imprimeur, 1997. En particulier, p. 53 : «la libre contemplation de la nature dans son ensemble – qui, depuis les Grecs et des siècles durant, faisait seule l’objet de la

philosophie – trouve dans l’intérêt de l’esprit pour la nature en tant que paysage une structure et une forme nouvelles».

1 - This point recalls the fine analysis of Joachim Ritter in Paysage: Fonction de l’esthétique dans la société moderne [Landscapes: the function of the aesthetic in modern society], Besançon, Editions de l’imprimeur, 1997. See p. 53 in particular: “free contemplation of nature as a whole — which has been philosophy’s only object, from the time of the Greeks and through the intervening centuries — finds a structure and a new form in the mind’s interest in nature as landscape”.

2 - G. Simmel, «Philosophie du paysage», in Tragédie de la culture, Paris, Rivages-Poches, 1988, p. 232.

2 - Georg Simmel, “Philosophie du paysage [Philosophy of the landscape]”, in Tragedie de la culture, Paris, Rivages-Poches, 1988, p. 232.

3 - P. Descola, Par-delà nature et culture, Paris, Gallimard, 2005, p. 94 : «une telle "objectivation du subjectif" produit un double effet : elle crée une distance entre l’homme et le monde tout en renvoyant l’homme à la condition de l’autonomisation des choses, elle systématise et stabilise l’univers extérieur tout en conférant au sujet la maîtrise absolue sur l’organisation de cette extériorité nouvellement conquise».

3 - Philippe Descola, Beyond Nature and Culture, trans. Janet Lloyd, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013, p. 59-60: “Such an ‘objectivization of the subjective’ produces a twofold effect: it creates a distance between man and the world by making the autonomy of things depend upon man; and it systematizes and stabilizes the external universe even as it confers upon the subject absolute mastery over the organization of this newly conquered exteriority”.

4 - Dans son essai magistral sur cette séparation de l’homme et de la nature, de la ville et de la campagne, notamment dans sa lecture du poème de Schiller, «La Promenade», Joachim Ritter a insisté à propos de la naissance esthétique du paysage qu’«Etant la nature visible propre à l’existence terrestre ptoléméenne, le paysage procède donc à la fois historiquement et objectivement du divorce qui caractérise la structure de la société moderne» cf. Paysage, op. cit., p. 81.

4 - In his masterly essay about this cleft between human beings and nature, the city and the country, and especially in his reading of Schiller’s poem “The Walk”, Ritter highlights that in the aesthetic birth of the landscape, the latter, “[a]s visible nature inherent in terrestrial Ptolemaic existence, proceeds both historically and objectively from the divorce that typifies the structure of modern society” cf. Paysage, op. cit., p. 81.

5- Si avant le XVème siècle, il existe très peu de paysages peints ou décrits, peut-être est-ce à cause du sentiment général d’appartenance sensible des hommes à leur contrée ? La séparation avec le milieu ambiant que provoque la nouvelle image du monde, géographique, précapitaliste et préscientifique, rend possible la naissance du paysage.

5- If so very few landscapes were painted or described before the fifteenth century, perhaps this is because people then generally felt that they belonged among those from their own land. The new geographical, precapitalist and prescientific image of the world provoked a separation from the ambient milieu, and this change made the birth of the landscape possible.

6- Cf. Jean-Marc Besse, Face au monde. Atlas, jardins, géoramas, Paris, Desclée de Brouwer, 2003, p. 169.

6 - See Jean-Marc Besse, Face au monde. Atlas, jardins, géoramas [In Front of the World: Atlases, Gardens, Georamas], Paris, Desclée de Brouwer, 2003, p. 169.

7 - G. Simmel, «Philosophie du paysage», in La tragédie de la culture, op. cit., p. 241.

7 - Simmel, “Philosophie du paysage”, in La tragédie de la culture, op. cit., p. 241.

8 - Ibidem, p. 231.

8 - Ibid., p. 231.

9 - Ibidem, p. 243.

9 - Ibid., p. 243.

10 - Ibidem, p. 242.

10 - Ibid., p. 242.

11 - Ibidem, p. 242.

11 - Ibid., p. 242.

12 - Cézanne, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, collection "Encre marine", 2012, p. 153. De même, p. 156 : «Il y a une minute du monde qui passe. La peindre dans sa réalité ! Et tout oublier pour cela. Devenir elle-même. Etre alors la plaque sensible. Donner l’image de ce que nous voyons en oubliant tout ce qui a paru avant nous».

12 - Joachim Gasquet, “‘What He Told Me…’ (excerpt from Cézanne, 1921)”, in Conversations with Cézanne, ed. Michael Doran, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2001, p. 113. Also see p. 115: “A minute of the world goes by. To paint it in its reality! And to forget everything else. To become reality itself. To be the photographic plate. To render the image of what we see, forgetting everything that came before.”.

13 - Ibidem, p. 150 : «Le paysage se reflète, s’humanise, se pense en moi. Je l’objective, le projette, le fixe sur ma toile».

13 -Ibid., p. 110: “The landscape is reflected, becomes human, and becomes conscious in me. I objectify it, project it, fix it on my canvas.”

14 - Ibidem, p. 154. Elle n’est pas contradictoire avec le projet de faire de l’impressionnisme quelque chose de solide et de durable. La recherche du géologique et du géométrique chez Cézanne ne contredit pas son atmosphérisation de l’être, elle participe d’une même volonté d’abandonner la surface pour la profondeur. La couleur, la lumière, l’air organisent le monde et le tableau, leur donnent une assise : ils jouent donc le même rôle de structure fondamentale que les éléments solides de la terre.>

14 -Ibid., p. 114. This does not contradict the effort to turn impressionism into something solid and lasting. Cézanne’s geological and geometrical research does not conflict with his way of making being atmospheric; instead, it participates in the same determination to renounce the surface for the sake of depth. Both world and painting are organized around color, light and air, which provide their foundation; they thus have the same role of fundamental structure as do the solid features of the Earth.

Traduction John Holland