- works

- installations

- texts

- books

- videos

- publications

- events

- bio

- contacts

DAMIEN SAUSSET

Extrait de la monographie "Transfigurations" chez Filigranes

Nul ne semblait se soucier de sa lente agonie comme si l’évidence de sa prochaine disparition paraissait trop improbable pour être possible. Pour ceux là, le terme de mutation était préférable, masquant ainsi une profonde candeur envers un futur qu’ils estimaient forcément riche de promesses. D’autres, au contraire, s’alarmaient, réclamant des actions immédiates, comme si l’acte de décès pouvait être différé. L’espace occidental, car il s’agit bien de lui, ne porte plus la rassurante stabilité qui fut la sienne depuis la Renaissance. Il est désormais mouvant, sans consistance, traversé par des forces qui le plient, le contraignent. Il ne se comporte plus comme cette étendue dans laquelle il fallait se situer ou se positionner, comme si le dialogue étroit que les hommes entretenaient depuis toujours avec la réalité était dissous. L’espace se fait virtuel. Il est traversé par des flux, par les autoroutes de la communication, autant de phénomènes abolissant les bornes géographiques. Désormais, il devient plus facile de communiquer avec le bout du monde qu’avec certaines régions de notre pays tout comme la circulation entres les métropoles – via un réseau efficace de liaisons intercontinentales – se révèle plus aisée que de rallier certains coins des départements français. Même le paysage semble faire défaut. L’habitat vernaculaire qui autrefois reflétait une conception de l’univers tout autant qu’un système de techniques liées aux possibilités du sol s’est effacé, laissant place à une architecture normalisée quasiment identique à l’autre bout de la planète. Faut il pour autant chanter ce lamento sur la perte des repères, composer à nouveau un requiem sur l’effacement des frontières entre espace public et sphère de l’intime ? Beaucoup s’y sont essayés, décrivant en détails les forces à l’œuvre. Mais dans ce concert d’analyses, il revient à quelques rares intellectuels, philosophes, architectes ou artistes d’avoir réussi à cerner la nouvelle nature de l’espace contemporain pour nous le présenter sans les artifices de la fiction.

None seemed overly concerned by its slow agony, as if the evidence of its forthcoming passing seemed too improbable to be possible. For those, the term mutation was prefered, thus masking a profound candor towards a future they imagined necessarily rich with promise. Others, on the contrary, were alarmed, demanding immediate action, as if that very passing might be postponed. The western space, for that is what we are talking of, no longer carries with it the reassuring stability that had characterized it since the Renaissance. It is henceforth shifting, inconsistent, traversed by forces to which it yields, or that constrain. It no longer acts as that vast expanse in which one must be situated or take position, as if the close dialogue that men have always entertained with reality had dissolved. Space has became virtual. It is traversed by fluxes, by highways of communication, so many phenomenons that abolish geographical markers. Henceforth, it has become easier to communicate with the other end of the world than with certain areas of our own country, just as circulation between the big cities- via an efficient network of intercontinental liaisons – transpires to be easier than reaching the corners of some French departments. Even the landscape seems deficient. The vernacular habitat, that previously reflected a conception of the universe as much as a system of techniques related to the lay of the ground, has effaced itself, giving way to a a normalized architecture that is almost identical at the other end of the planet. Yet does this mean that we must sing a lament to this loss of bearings, compose a requiem on the disappearing of the frontiers between public space and the realm of the intimate? Many have tried to do so, describing in detail the forces at work. But within this concert of analyses, there are but a few rare intellectuals, philosophers, architects or other artisans who have succeeded in pinning down the new nature of contemporary space and presenting it to us without resorting to the artifices of fiction.

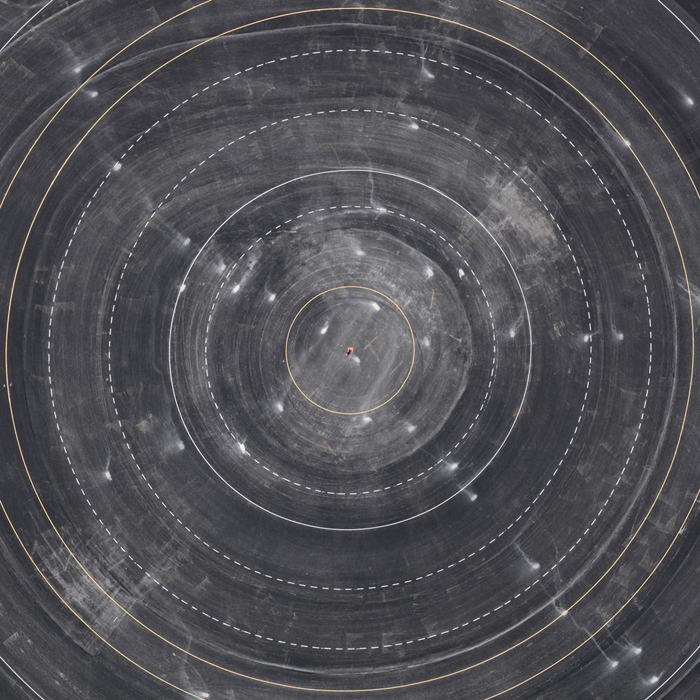

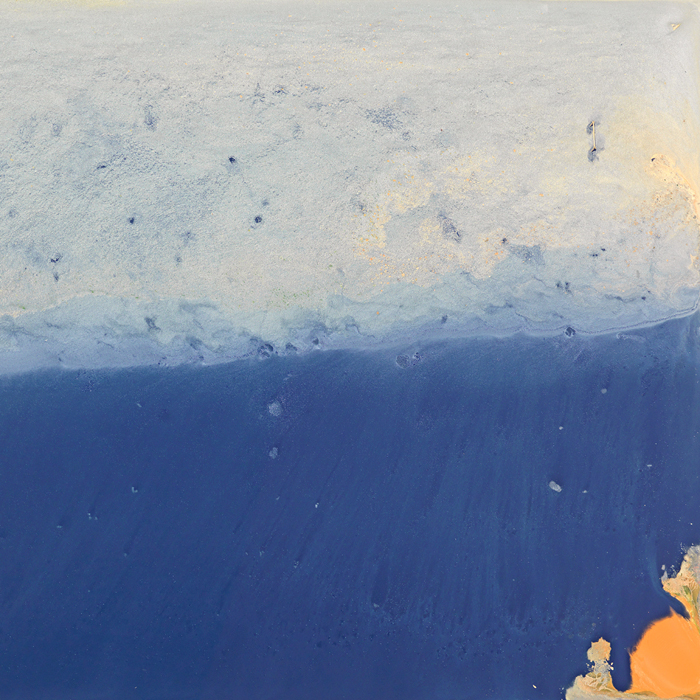

Jérémie Lenoir fait partie de ceux là. Contrairement à certains de ces contemporains , il serait vain de chercher dans ses œuvres une quelconque dénonciation. Ce qu’il enregistre depuis quelques années avec les moyens de la photographie est un état des lieux, une simple mise en forme de ce qu’il observe depuis l’avion d’où il réalise ses prises de vues. A priori, chacune de ses images présente un morceau de territoire . Ici, un champ cultivé, là un immense parking ou un chemin serpentant entre des zones marécageuses. La plupart demeurent mystérieuses. Difficile de comprendre ce que l’objectif a saisi, cerné, composé. L’œil s’égare, cherche quelques détails signifiants, tentant de lire le chromatisme comme autant d’indices propre à révéler la nature du réel. L’exercice est d’autant plus troublant qu’il est parasité par notre expérience du terrain, par la mémoire, par ces codes appris lors des voyages en avion. Qui n’a jamais passé de longues heures penchées sur le hublot, contemplant ce travelling infini sur le monde ? Qui s’est s’interrogé pour savoir si ces minces filets d’argent témoignent effectivement de rivières reflétant le soleil ? si ces zones sombres mouchetant le sol attestent des contreforts d’un simple relief ou d’une chaine montagneuse imposante ? Et cette ville ? quelle est son importance ? petite bourgade ou centre industriel ? Vues des hautes altitudes, même les métropoles prennent un air confiné, presque étriqué. Dans ces moments de pures contemplations, le sol devient un rébus, presque un labyrinthe que nous contemplons tel Icare puis confrontons avec nos connaissances géographiques. L’exercice est d’autant plus troublant que d’autres images viennent en mémoire : celles désormais banales de la terre vue de l’espace. Google Earth demeure l’un des sites les plus visité au monde et les vues qu’il propose ont durablement contaminé notre imaginaire . Face à ces images, le mystère demeure et nous nous retrouvons dans la situation de ce paysan décrit par Malraux dans L’Espoir. Embarqué par des aviateurs républicains pour leur indiquer les positions fascistes, l’homme qui arpentait chaque coin et recoin de son pays, pleure de ne rien reconnaître. Seul le survol à très basse altitude lui permet soudain de retrouver ses repères.

Jérémie Lenoir is one of them. Unlike some of his contemporaries1, it would be vain to seek any form of denunciation in his works. What he has recorded over several years with the photographer’s means is an inventory, a simple framing of what he observes from the airoplane from which he takes his shots. A priori, each of his images presents a portion of territory2. Here, a cultivated field, there an immense car-park or a path winding through marshy zones. Most remain mysterious. It is difficult to comprehend what the lens has captured, picked out, composed. The eye wanders, seeking out the few minor details, trying to read the chromaticism, so many clues that might reveal the nature of this reality. The exercise is that much more troubling in that it is contaminated by our experience of the terrain, by memory, by codes learnt on airoplane journeys. Who has never spent long hours bent over the window, contemplating this infinite tracking over the world? Who hasn’t wondered at whether those thin lines of silver are effectively traces of rivers reflecting the sun? If the dark areas spotting the ground signify the buttress of a simple slope or an imposing mountain chain? And this town? Of what importance is it? A small town or an industrial center? Viewed from a high altitude, even big cities take on a confined air, almost meagre. In these moments of pure contemplation, the ground becomes a puzzle, almost a labyrinth that we contemplate like Icarus, then to be confronted with our geographical knowledge. The exercice is even more troubling in that other images come to mind: those henceforth banal of the Earth seen from space. Google Earth remains one of the most visited websites in the world and the views it proposes have lastingly contaminated our imaginary3. Faced with these images, the mystery remains, and we find ourselves in the situation of the peasant described by Malraux in Man’s Hope : embarked by republican aviators to help indicate fascist positions, the man who had yet covered every nook and cranny of his country, cried because he recognized nothing; only flying over at very low altitude suddenly allowed him to regain his bearings.

Sauf que le mouvement de rapprochement de Jérémie Lenoir produit l’effet inverse. Ses images déploient une proximité. L’artiste insiste d’ailleurs sur ce point. L’altitude idéale est 1500 pieds (460 mètres). Au-dessous, les détails se font trop insistants. Plus haut, le paysage perd une certaine évidence pour devenir simple motif organique. La procédure ne vise pas à l’analyse exhaustive. Jérémie Lenoir n’interroge pas ce fameux territoire français même s’il convient que ces photographies attestent d’un moment précis de l’histoire de notre pays. Sur certaines, surgissent des aménagements techniques. Aucun n’est proprement signifiant. Pas d’échangeurs routiers, pas d’infrastructures imposantes ou de nouvelles marges urbaines (en cela, son nouveau travail radicalise les séries précédentes). Cet artiste n’enregistre pas plus les formes de résistance aux mutations du paysage. On ne trouvera pas chez lui ces petits villages symbolisant une France en voie de disparition avec un clocher et son semis de maisons traditionnelles. De même, ces chemins rocailleux, ces hautes haies, ce découpage presque aléatoire des champs, bref tous ces signes attestant de la longue histoire de la propriété foncière dans notre pays, sont étrangement absents. Le territoire qu’il vient de couvrir reste abstrait, presque désincarné. Or, c’est presque 2000 km2 que l’artiste a survolé autours d’Angers. D’un côté la Loire, ancien fleuve royal, voie de communication essentielle du Moyen-Âge au XIXe siècle. De l’autre, l’autoroute A85/A 11, axe de communication débouchant sur la Bretagne et les côtes de la Vendée. Soit une bande de territoire de 100 km de long sur 20 de large. Or, rien ne vient témoigner de l’enracinement de ce travail. Aucune image du fleuve, ni même d’aménagement technique lié à la construction du réseau routier. Seul subsiste des zones intermédiaires, sans attaches, soigneusement choisies par l’artiste.

Yet the way in which Jérémie Lenoir’s closes in produces the opposite effect. His images expose a proximity. The artist insists, for that matter, on this point. The ideal altitude is 1 500 feet (450 meters). Below that, the details are too insistant. Higher, the landscape loses a certain evidence to become a simple organic pattern. The procedure doesn’t aim for exhaustive analysis. Jérémie Lenoir isn’t questioning the famous notion of the French territory, even if he admits that his photographs attest to a precise moment in the history of our country. In some, technical developments appear. None is actually significant. No motorway bypasses, no imposing infrastructures nor new urban fringes (in that, his new work radicalizes the previous series). Nor does this artist record forms of resistance to the mutations of the landscape. In his work we do not find small villages with a church spire and its sprinkling of traditional houses symbolizing a France that is in the process of disappearing. In the same way, the rocky paths, high hedges, the almost random shape of the fields,in short, all those signs that otherwise attest to the long history of land ownership in our country, are strangely absent. The territory that he has covered remains abstract, almost uninhabited. And yet, it is a surface of almost 2 000 km2 that the artist has flown over around Angers. To one side the Loire, former royal river, an essential communication channel from the Middle Ages to the 19th century. On the other, the A85/A11 motorway, a communication axe leading both to Brittany and the Vendée coast. Or a strip of land 100km long and 20 wide. And yet, nothing bears witness to the localized aspect of this work. No images of the river, nor even of the technical developments linked to the construction of the road network. All that remains are the intermediary zones, otherwise unattached, carefully chosen by the artist.

On pourrait donc avancer l’hypothèse qu’il y a chez cet artiste la volonté farouche de vouloir réinventer une possibilité du paysage, de le faire exister par d’autres moyens que ceux, ordinaires, d’une figuration jouant avec les codes figés de la photographie . En ce sens, ces images n’ont que faire des strates historiques qui feraient normalement la joie des géographes et historiens. Leur motif est autre, leur raison d’être différente. En d’autres termes, les photographies de Jérémie Lenoir se situent à la croisée de plusieurs chemins. Elles doivent être comprises comme des interrogations sur notre monde tout autant que des réalisations prenant en compte la longue histoire de la peinture ou de la photographie. En cela, cet artiste active un réalisme nouveau, à la fois tributaire d’une objectivité renouvelée tout autant que d’une mise en forme distanciée de l’image photographique.

One might then advance the hypothesis that the artist has a strong desire to reinvent a possibility of landscape, to make it exist by means other than the ordinary ones of figuration which play with the fixed codes of photography4. In this sense, his images have no use for the layers of history that are normally the joy of geographers or historians. Their motive is other, their reason for being, different. In other terms, Jérémie Lenoir’s photographs are situated at a crossroads of several paths. They should be understood as interrogations of our world as much as creations that take into account the long history of painting and photography. In that, the artist activates a new realism, at the same time tributary of a renewed objectivity as much as a distanced shaping of the photographic image.

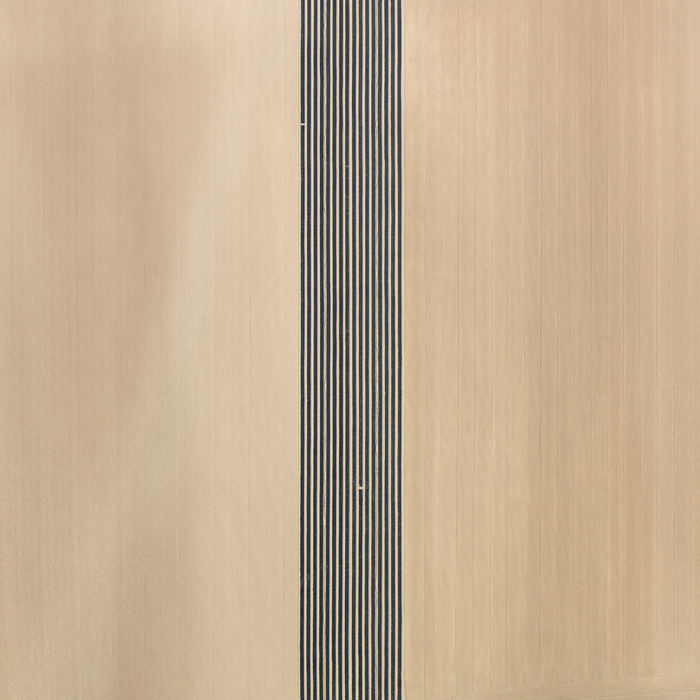

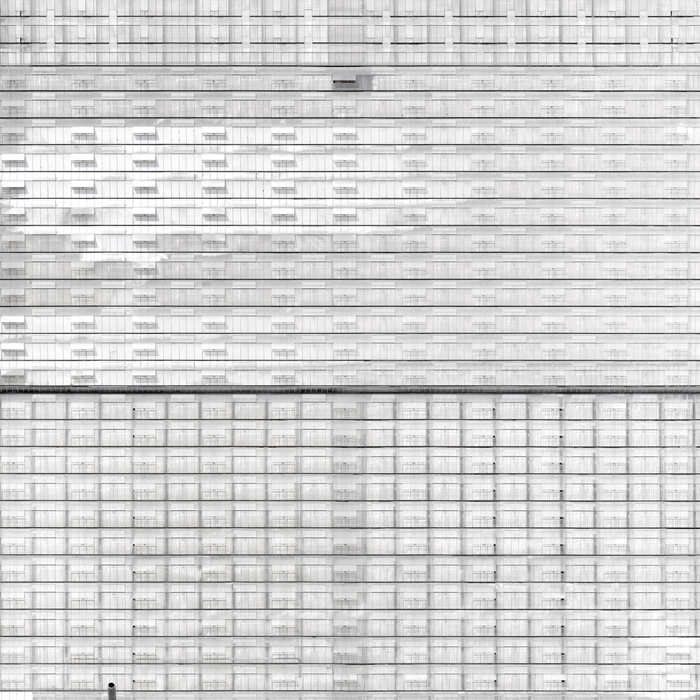

L’un des traits majeurs de cet art est son absolue planéité. Le relief en est absent comme en atteste la difficulté pour chaque spectateur de reconstituer les profondeurs et les volumes. Ces photographies ne comportent aucune charte, aucune légende. Elles se présentent comme les antithèses des cartes géographiques ou divers codes rétablissent les spécificités du terrain. Ce qui est là semble plat. D’ailleurs, l’artiste a pris soin de les réaliser aux heures précises ou le soleil à son zénith abolie les ombres, les courbures du terrain, laissant à nu un sol qui se réduit désormais à de simples variations colorées, certaines informelles, d’autres géométriques. L’image photographique se présente comme une simple surface striée, contaminée, parasitée par quelques détails signifiants. Mais si peu.

One of the major characteristics of this art is its absolute flatness. Any relief is absent, as attested by the difficulty the spectator has in reconstituting the depths and volumes. These photographs aren’t accompanied by charts, or captions. They present themselves as the antitheses of geographical maps in which various codes reestablish the specificities of the terrain. What is there seems flat. Come to that, the artist has been careful to take them at the precise times when the sun at its zenith abolishes the shadows, the curves of the land, leaving naked a ground that is reduced to simple colored variations, some informal, others geometric. The photographic image presents itself as a simple striped surface, contaminated, interrupted by a few minor details. Yet so few.

Cette planéité n’est pas inédite. Elle court tout au long de l’histoire de la photographie. Et si certaines images plates depuis l’invention de la photographie ressortent du pur hasard, dans nombre de cas, la planéité sert à activer un regard critique sur le monde, énonçant ainsi un rapport au réel marqué par les enjeux formels typiquement picturaux. Il revient à Eric de Chassey d’avoir isolé ce mouvement souterrain dans un ouvrage récent : Platitudes, une histoire de la photographie plate. Il y constate combien cette absence de profondeur, « attire l’attention sur leur caractère de surfaces – pour le dire d’un mot, des images plates, tant du point de vue spatial (l’image s’y présente avant tout comme une surface bidimensionnelle) que temporel (la durée y est suspendue sans suggérer la moindre amorce de narrativité)…». Cette volonté d’accentuer le rôle de la surface du tirage photographique n’est sans doute pas innocent. Enregistrement technique captant l’illusion de la profondeur, la photographie devient plate aux conditions express de se mesurer à la fois aux spécificités du médium et à un horizon de lecture particulier. En d’autres termes, Bols (1916) de Paul Strand diffère radicalement de Corrugated Tin Façade (1936) de Walker Evans ou Kühlturm, Bochum, Ruhrgebiet (1959) de Bernd et Hilla Becher, trois exemples parmi d’autres de platitude en photographie. Comme le remarque Eric de Chassey, Strand tente de concilier planéité et profondeur spatiale selon l’exemple du cubisme de Picasso qu’il venait de découvrir. La diffraction des plans réduits la série de bols à un jeu de courbes et contre-courbes. Seuls les valeurs de noir et de blanc permettent de maintenir l’unité de la représentation. Dans le second cas, on peut avancer qu’Evans recherche un parti pris formel le plus neutre et le plus banal possible, propice à la mise en place de son fameux style documentaire. La vue frontale entraine une neutralisation du motif tout autant que la mise à distance de ses éléments externes (le paysage). Quant au principe typologique des Becher (l’enregistrement quasi archéologique d’un bâti industriel en voie de disparition depuis les hauts-fourneaux jusqu’aux châteaux d’eau), il répondait à la subjectivité des émules d’Otto Steiner, présenté dès les années 1950 comme le héros d’un retour aux expérimentations de la photographie allemande des années 1920, c’est-à-dire avant l’irruption du National Socialisme. Pour les Becher, un tel enthousiasme envers une subjectivité débridée (repérant dans le réel les éléments les plus pittoresques) reposait sur un déni de l’histoire douloureuse de l’Allemagne et un refus du présent. La planéité de l’image (motif centré, refus de toute ombre, point de vue élevé…) renforce le caractère commun de l’objet saisi (en l’occurrence une architecture) tout en affirmant le contenu idéologique du bâti : une certaine adhésion à un projet moderniste si caractéristique de la première moitié du XXe siècle.

This flatness is not new. It runs throughout the whole of the history of photography. And if some flat images since the beginning of photography have been born from pure chance, in many cases the flatness actually serves to activate a critical eye on the world, thus spelling out a relationship to reality marked by typically pictorial formal concerns. It was Éric de Chassey5 who recently isolated this underlying movement in a recent work: Platitudes, une histoire de la photographie plate. He notes the way in which this lack of depth «attracts the attention to their character as surfaces – to put it in a word, flat images, both from a spatial point of view (the image is presented above all as a two-dimensional surface) and temporal (the time-span is suspended without suggesting the slightest element of narration) [...] ». This will to accentuate the role of the surface of the photographic print is no doubt deliberate. A technical recording capturing the illusion of depth, photography becomes flat on the express conditions of measuring itself both against the specificities of the medium and a particular horizon of interpretation. In other terms, Bowls (1916) by Paul Strand, differs radically from Corrugated Tin Façade (1936) by Walker Evans or Kühlturm, Bochum, Ruhrgebiet (1959) by Bernd and Hilla Becher, three examples amongst many others of flatness in photography. As Éric de Chassey remarks, Strand tried to conciliate flatness and spatial depth according to the example of Picasso’s cubism that he had just discovered. The diffraction of planes reduces the series of bowls into a play of curves and counter-curves. Only the tones of black and white maintain the unity of the representation. In the second case, one can advance that Evans is seeking the most neutral and the most banal formal parti pris possible, propitious to setting in place his famous documentary style. The frontal view leads to a neutralization of the subject as much as a distancing of its external elements (the landscape). As to the Becher’s typlogical principle (the almost archeological recording of an industrial building in the process of becoming extinct, from blast-furnaces to water-towers), it was in response to the subjectivity of the followers of Otto Steinhart, presented as early as the 1950s as the hero of a return to the experimentations of German photography of the 1920s, that is to say before the irruption of National-Socialism. For the Bechers, this enthusiasm for an unbridled subjectivity (picking out the most picturesque elements in reality) reposed on a denial of Germany’s painful history and a refusal of the present. The flatness of the image (a central motif, a refusal of shadows, elevated view-point…) reinforces the common character of the object captured (in this case architecture) while affirming the ideological content of the building: a certain adhesion then to a modernist project so characteristic of the first half of the 20th century.

Bien que conscient de ces modèles (qu’il faudrait sans doute compléter), Jérémie Lenoir a su intégrer dans ses compositions d’autres exemples. D’une certaine manière, ses photographies participent bien plus d’une attitude pop. On sait aujourd’hui, combien la peinture du pop art répondait à un impératif de platitude. Ce qui importe alors, c’est de lutter contre «la profondeur émotionnelle de l’abstraction lyrique tel Pollock» comme l’avoue en 1968 Lichtenstein lors d’une interview avec Alain Robbe-Grillet. Or, s’il est un point sur lequel tous les critiques s’accordent, c’est bien cette absence absolue de lyrisme dans les photographies de Jérémie Lenoir. Ses motifs ne comportent aucune emphase si ce n’est l’extrême richesse d’une palette chromatique puisée dans le réel. Comme tant d’autres photographes de sa génération, l’attitude pop consiste chez lui à refuser la spontanéité, l’émerveillement ou l’ironie. D’une certaine manière cette attitude pop n’était que la reprise appliqué à l’image de la tradition descriptive inaugurée par Flaubert (et dont Robbe-Grillet se voulait l’héritier). Ce vieux fond littéraire a sans doute permis consciemment ou inconsciemment à Jérémie Lenoir de repérer les impasses du pop art américain, dont celle essentielle que toutes ses représentations renvoient à une spécificité de la culture américaine : le vernaculaire s’y érige en spectacle (magnifié par l’environnement commercial et médiatique). Là réside la leçon des toiles de Warhol mais aussi des photographies faussement banales du plus pop des artistes de la côte ouest : Edward Ruscha. Dès 1963, ce dernier réalise de petits ouvrages constitués de photographies banales. Le premier Twenty six Gasoline Station (1963) présente 26 vues de stations services. Seul l’étonnant Thirty four Parking Lot de 1967 transcende la critique implicite de la culture véhiculée par le pop art. Là encore, les images se veulent anti-héroïques. L’information est réduite à son strict minimum et présente 34 parkings vus depuis le ciel. Mais à la différence des ouvrages précédents, ce petit opus énonce d’autres vérités. Les dessins ordonnés des bandes blanches construisent au final un motif abstrait, un véritable tableau noir et blanc ou la réalité n’affleure qu’après une étude attentive des marges de l’image. La flexibilité de la vision fragmentaire (image réalisée depuis un point de vue élevé et composé avec soin) se plie à la stabilité ordonnée de la composition. D’une certaine manière, cet exemple de photographies montrait la voie à un art plus ambivalent, un art ou la description se situe entre visible et invisible, un art enfin capable de convoquer l’histoire sans pour autant en faire le sujet même (ce qui faisait défaut aux sujets du pop art souvent puisés dans l’actualité) . D’autres artistes ont également parfaitement intégré la leçon. Ainsi Sophie Ristelhueber avec sa série Fait (1991) montre, vue du ciel, les traces récentes de la guerre dans le désert du Koweït. Les tranchées, ouvrages de défenses, cratères d’obus y apparaissent comme autant de signes ambivalents : tableaux abstraits ou cicatrices faites à un paysage symbolisant ainsi celles, terribles, faites aux corps des combattants. Rien de tel chez Jérémie Lenoir. On ne retrouve chez lui aucune évocation distanciée d’un événement politique et médiatique. La raison d’être de ses images est autre. La platitude lui sert à dupliquer le modèle pictural, notamment celui de la peinture abstraite du milieu du XXe siècle. Il est à noter que ces préoccupations n’auraient été possible sans sa connaissance de l’art du paysage au XIXe siècle qui voyait un genre s’épanouir avant d’entrer durablement en crise (du romantisme à l’impressionnisme en passant par le naturalisme) . Toute la pratique de Jérémie Lenoir consiste justement à déjouer – et même inverser – l’imaginaire du XIXe siècle en utilisant à la fois la rhétorique de l’art abstrait et les possibilités formelles de la photographie.

If conscious of these models (that no doubt require completion), Jérémie Lenoir has been able to integrate other examples into his compositions. In a way, his photographs participate rather in a pop attitude. We know today the extent to which pop art painting responded to an imperative of flatness. What matters then, is the struggle against « the emotional depth of lyrical abstraction, like Pollock » as Lichtenstein admitted in 1968 in an interview with Alain Robbe-Grillet. And yet, if there is one point upon which all critics agree, it is the absolute absence of lyricism in Jérémie Lenoir’s photographs. His subjects bear no emphasis if not the extreme richness of a chromatic palette drawn from reality. Like so many other photographers of his generation, the pop attitude consists for him in a refusal of spontaneity, wonderment or irony. In a way this pop attitude was but a return, applied to the image, of the descriptive tradition inaugurated by Flaubert (and to which Robbe-Grillet considered himself the heir). These old literary foundations no doubt consciously or unconsciously helped Jérémie Lenoir to perceive the impasses of American pop art, including the essential one that all its representations make reference to specificities of American culture (magnified by the commercial and mediatic environment). Therein resides the lesson of Warhol’s paintings, but also of the falsely-banal photographs of the most pop of the west-coast artists: Edward Ruscha. As early as 1963, the latter created small works made up of ordinary photographs. The first, Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963), presents 26 views of service-stations. Only the astonishing Thirtyfour Parking Lots, from 1967, transcends the implicit criticism of culture vehicled by pop art. There again, the images intend to be anti-heroic. The information is reduced to its strict minimum and presents thirty-four car-parks seen from the sky. But unlike the previous works, this small opus also spells out other truths. The rigorous drawings of the white strips in the end build up an abstract pattern, a veritable black and white painting in which reality only shows through after an attentive study of the edges of the image. The flexibility of the fragmentary vision (image created from an elevated viewpoint and carefully composed) yields to the organized stability of the composition. In a certain manner, this example of photographs showed the way to a more ambivalent art in which description is situated between the visible and the invisible, an art finally capable of convoking history without yet making it the actual subject (deficient in pop art subjects, often drawn from the news)6. Other artists also integrated this lesson perfectly. Thus Sophie Ristelhueber with her series Fait (1991) shows, seen from the sky, the recent traces of the war in the Koweit desert. The trenches, defence constructions and bomb craters appear there as so many ambivalent signs: abstract paintings or scars caused on a landscape that thus symbolize those, terrible, inflicted on the bodies of the fighters. There is none of this with Jérémie Lenoir. In his work we find no distanced evocation of a political or media event. The raison d’être of his images is other. The flatness serves him to duplicate the pictorial model, notably that of abstract painting from the middle of the 20th century. It is to be noted that these preoccupations would not have been possible without his knowledge of the art of landscape from the 19th century, which saw the flourishing of a genre before lastingly entering a crisis (from Romanticism to Impressionism via Naturalism)7. All of Jérémie Lenoir’s practice consists precisely in foiling – and even reversing – the imaginary of the 19th century by using both the rhetoric of abstract art and the formal possibilities of photography.

Toutes ses compositions favorisent les croisement orthogonaux ou les pénétrations en diagonales. Le rabattement radical des plans à une simple surface détruit toute idée de hors champ, cette spécificité de l’image photographique. Tout est dedans. L’image est à la fois un fragment et une totalité. Ce jeu subtil emprunte évidemment sa forme à la peinture, plus spécifiquement à la grande peinture abstraite tel qu’elle s’est développée des années 1930 aux années 1950 . Si certaines de ses photographies favorisent un all-over qui n’est pas sans évoquer à la fois la peinture informelle européenne et certaines tendances de l’art abstrait américain (tel Clyfford Still), d’autres en revanche affirment clairement leurs dettes aux tendances les plus construites de l’abstraction géométrique (Mondrian en tête) . La question du format est donc essentielle pour lui. Ses tirages (180 x 180 cm ou 65 x 65 cm) renvoient explicitement au format tableau, à cette idée que seul la frontalité de l’image suspendue et son autonomie peuvent conduire à une expérience de confrontation. Jérémie Lenoir ne découpe pas une fenêtre dans le monde déployé comme un spectacle. Il ne cherche pas à se saisir des grandes scènes de la nature comme ce fut le cas avec la peinture du XIXe siècle (et ses effets de sublime ou de pittoresque). Au contraire, ce qu’il produit résulte d’un double processus : celui d’images qui renvoient explicitement à un référent (un paysage vue du ciel) et le fait que chacune se lise également comme des constructions spéculatives. D’ou chez lui l’importance de la série. Pour atteindre l’efficacité voulue, sa pratique nécessite la mise en place d’une déclinaison, d’un nombre minimum d’exemples permettant au spectateur de s’arracher définitivement du référent photographique. L’idée de série comporte un autre avantage : elle contredit définitivement l’idée d’héroïsme propre à la peinture abstraite. Chaque image fonctionne donc comme un tableau d’expérience, comme une force d’interruption et même une forme de résistance au déroulement du spectacle des médias. C’est d’ailleurs pour cette raison qu’il déplie ce travail dans une installation monumentale de 35 mètres de long. Non seulement le spectateur expérimente chaque image, mais il ouvre, grâce à la déambulation et la marche, un nouvel espace. Il rejoue l’espace des photographies dans la réalité de ses mouvements.

All his compositions favor orthogonal crossings or diagonal pentrations. The radical pulling-up of the planes to a simple surface destroys any idea of the out of shot, so specific to the photographic image. Eveything is within. The image is at the same time a fragment and a whole. This subtle game obviously borrows its form from painting, more specifically large abstract painting as it developed from the 1930s to the 1950s. If some of his photographs favor an all-over which is not without evoking both European informal painting and certain tendencies of American abstract art (see Clyfford Still), others on the contrary clearly confirm their debt to the more constructed tendencies of geometric abstraction (Mondrian at their fore)8. The question of format is thus essential to him. His prints (180 x 180 cm ou 65 x 65 cm) explicitly make reference to those of paintings, to the idea that only the frontality of the suspended image and its autonomy can lead to an experience of confrontation. Jérémie Lenoir doesn’t cut out a window in a world spread out in a spectacle. He doesn’t seek to capture grandiose scenes of nature as was the case in 19th century painting (with its effects of the sublime or picturesque). On the contrary, what he produces results from a double process: that of images that explicitly refer back to a reference (a landscape seen from the sky) and the fact that each one can also be read as a speculative construction. From whence with him the importance of series. To attain the desired effectiveness, his practice requires the setting up of a range, of a minimum number of examples that allow the spectator to definitively tear himself away from the idea of heroism proper to abstract painting. Each image functions then as a painting of an experience, like a force of interruption and even a form of resistance to the unfolding of the spectacle of the medias. It is, come to that, for this reason that he chose to display this work in a monumental installation of 35 meters long. Not only the spectator experiences each image, but, thanks to the actions of deambulation and of walking, he opens up a new space. He replays the space of the photographs in the reality of his own movements.

C’est d’ailleurs ces qualités qui permettent de saisir toute la différence entre les photographies de Jérémie Lenoir et les illustrations de Yann Arthus Bertrand, photographe au registre voisin. Ce dernier ne cesse de mettre en scène un pathos de l’émerveillement. Il y a chez Yann Arthus Bertrand l’idée rassurante que le monde recèle en lui cette beauté mièvre propre aux contes, aux histoires merveilleuses. En d’autres termes, il suggère que ses images, face à la décrépitude de la culturelle contemporaine, portent un imaginaire de la nature comme plénitude miraculeuse ou perdue. Or, ces visuels fonctionnent selon la rhétorique propre à la publicité et aux formes de communication contemporaines. Toutes se présentent comme des découpes dans un monde déployé comme un spectacle, comme une féérie théâtrale. Ce message se révèle d’autant plus pervers qu’il se présente sous la forme d’une alerte : la diversité de la terre risque de disparaître. Evidemment un tel évangélisme (avec pour corolaire l’idée romantique d’un artiste démiurge capable de révéler une beauté cachée) fonctionne sur les bas instincts d’une culture judéo-chrétienne : voici venu le temps de la culpabilité, le temps où la planète nous présente la dette de nos pêchés. Sous-jacent, ces images laissent transparaitre cette sorte de vénération pour un temps primitif, vierge, ou tout paraît possible – et l’on sait combien l’imaginaire européen est encore sous le joug de cette malédiction responsable de tant d’atrocités commises au nom d’une origine à retrouver.

It is come to that these qualities that allow one to grasp the major difference between Jérémie Lenoir’s photographs and the illustrations of Yann Arthus-Bertrand, a photographer in a similar register. The latter constantly stages a pathos of wonderment. There is, in Yann Arthus-Bertrand’s work, the reassuring idea that the world holds within it that mawkish beauty of fairytales, of fantastical stories. In other terms, it suggests that his images, in the face of the decrepitude of contemporary culture, are bearers of an imaginary of nature as a miraculous or lost plenitude. Yet these visuals function according to a rhetoric that belongs to advertizing and contemporary communication. They present themselves like cut-outs of a world spread out like a spectacle, like a theatrical fairytale. This message reveals itself to be even more perverse in that it presents itself in the form of a warning: the earth’s diversity is at risk of disappearing. Obviously such evangelism (with for corollary the romantic idea of a demiurgic artist capable of revealing a hidden beauty) functions on the baser instincts of Judeo-Christian culture: here is the time of guilt, the time where the planet presents us with the bill for our sins. In a subjacent manner, these images give a glimpse of a sort of veneration for a primitive time, virgin, where everything was possible – and we know to what extent the European imaginary is still under the yoke of that very curse responsable for so many atrocities committed in the name of origins to be re-found.

Evidemment, les photographies de Jérémie Lenoir sont aux antipodes de cela puisqu’il ne cesse ne nous dire que la puissance souterraine des images, de ses images, repose sur une capacité d’étrangeté, sur une manière de nous entrainer dans un réel autre que celui miraculeux d’une possible rédemption (d’ailleurs on sait combien l’idée d’une rédemption par l’image est totalement impossible dans un monde structuré par les visuels). Face aux images de Jérémie Lenoir, certains seraient tentés d’y voir une prédilection morbide pour les espaces figés, déshumanisés, vides, autant de traits propices à la fascination. Il n’en est rien. L’autonomisation de la composition ne se fait pas au détriment du renvoi au réel. Simplement, la neutralisation du référent conduit à l’impossibilité de la figure humaine. L’image photographique devient un véhicule plat, ouvert par son abstraction à toutes les associations symboliques. C’est pour cette raison qu’il serait vain d’y chercher un soupçon de message explicite. On peut tout autant les percevoir comme des constats amères sur les aménagements de notre territoire, comme des méditations sur la disparition et la mort, des tentatives d’une réconciliation avec le monde, des variations savantes sur l’épuisement du médium photographique...

Obviously, Jérémy Lenoir’s photographs are at the antipodes of this, for he doesn’t cease to tell us that the underlying power of images, of his images, reposes on a capacity for strangeness, on a way of leading us into a reality other than the miraculous one of a possible redemption (and indeed we know how totally impossible is the idea of redemption through images in a world that is structured by visuals). In the face of Jérémie Lenoir’s images, some might be tempted to see a morbid predilection for spaces that are transfixed, dehumanized, and empty; so many traits that lend to fascination. This is not the case. The autonomization of the composition doesn’t take place to the detriment of the reference to reality. It is simply that the neutralization of references implies the impossibility of the human figure. The photographic image becomes a flat vehicle, opened up by its abstraction to all possible symbolic associations. It is for this reason that it would be vain to search for an explicit message. One can just as well perceive them as bitter observations on the developments of our territory, as meditations on disappearance and death, as attempts at a reconciliation with the world, or as savant variations on the exhausting of the photographic medium…

Chaque image de Jérémie Lenoir ne peut donc être réduite à une donnée miraculeuse, une trouvaille. L’homme sait ce qu’il veut, opère de longues heures avant de construire son image. Seul lui importe un soucis du cadrage et l’élégance de couleurs soudains révélées. L’élaboration prend un temps long, nécessitant de nombreux vols, conduisant même l’artiste à revenir quelques mois ou saisons plus tard. Question de lumière, de saillance de la végétation, de rapports chromatiques. Il faut reconnaître à Jérémie Lenoir d’avoir entrepris une véritable éducation du regard par la sensation. D’abord à travers le jeu des détails réaffirmant la pureté descriptive de l’enregistrement. Ensuite dans ce foisonnement de matières et de formes qui, en empruntant les chemins de l’abstraction, confirme la diversité et la complexité du visible. L’abstraction ne fonctionne pas ici dans l’opposition classique des plans d’ensemble et des détails, ni même dans la disparition des figures identifiables . Au contraire, elle surgit dans la qualité descriptive du regard et l’utilisation manifeste du cadre. C’est bien ce réalisme nouveau qui place Jérémie Lenoir dans la position difficile de devoir décrypter un monde qu’on dit globalisés. L’impératif critique se double ainsi chez lui d’une étude distanciée des habitudes de notre regard, de notre incapacité à saisir ce que cache véritablement une image. C’est là toute sa force, toutes ses limites aussi. C’est peu et beaucoup. Rares sont ceux qui y parviennent.

None of Jérémie Lenoir’s images can then be reduced to a miraculous given, or discovery. The man knows what he wants, operating over long hours before actually constructing his images. All that matters for him is the careful framing and the elegance of colors suddenly revealed. The process takes a long time, necessitating numerous flights, even leading the artist to come back several months or several seasons later. A matter of light, of the prominence of the vegetation, of chromatic rapports. One must recognize that Jérémie Lenoir has undertaken a veritable education of the eye through sensation. First of all through the play of details that re-affirm the descriptive purity of the recording. Then in the abundance of textures and shapes which, by borrowing the paths of abstraction, confirm the diversity and the complexity of the visible. The abstraction doesn’t function here in the classic opposition of views of the whole and details, nor even in the disappearance of identifiable figures9. On the contrary, it appears through the descriptive quality of the regard and the manifest use of the framing. It is indeed this new realism that places Jérémie Lenoir in the difficult position of deciphering a world that is said to be globalized. The critical imperative with him is thus paired with a distanced study of the habits of our ways of seeing, of our incapacity to grasp what an image truly hides. Therein lie his strength and also his limits. It is both little, and much. And it is a task in which few succeed.

Damien Sausset